When we get it wrong

It is a stunning piece of American history.

The first known written protest against slavery in what was to become the United States.

Just about every website that reports on things that happened on this day, February 18th, in history will tell you that today is the 332nd anniversary of the drafting and signing of the document known as the Germantown Petition.1

For The Legal Genealogist, for those researching Quaker history — indeed for any genealogist researching early American families, this is a powerful document, reading in part:

… (Y)e most part of such negers are brought hitherto against their will and consent and that many of them are stolen. Now tho they are black we cannot conceive there is more liberty to have them slaves, as it is to have other white ones. There is a saying that we shall doe to all men like as we will be done ourselves; making no difference of what generation, descent or colour they are. And those who steal or rob men, and those who buy or purchase them, are they not alike? Here is liberty of conscience wch is right and reasonable; here ought to be likewise liberty of ye body, … But to bring men hither, or to rob and sell them against their will, we stand against. … And we who know that men must not committ adultery,—some do committ adultery, in others, separating wives from their husbands and giving them to others; and some sell the children of these poor creatures to other men. Ah! doe consider well this thing, you who doe it, if you would be done at this manner? … This makes an ill report in all those countries of Europe, where they hear off, that ye Quakers doe here handel men as they handle there ye cattle. … Pray, what thing in the world can be done worse towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away, and sell us for slaves to strange countries; separating housbands from their wives and children. … (W)e contradict and are against this traffic of men-body. And we who profess that it is not lawful to steal, must, likewise, avoid to purchase such things as are stolen, but rather help to stop this robbing and stealing if possible. And such men ought to be delivered out of ye hands of ye robbers, and set free …

If once these slaves (wch they say are so wicked and stubborn men) should joint themselves — fight for their freedom, — and handel their masters and mastrisses as they did handel them before; will these masters and mastrisses take the sword at hand and warr against these poor slaves, licke, we are able to believe, some will not refuse to doe; or have these negers not as much right to fight for their freedom, as you have to keep them slaves?2

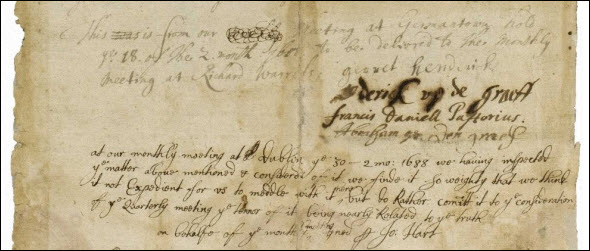

The protest was in fact signed by four men, all German Quakers in Germantown, Pennsylvania: Garret Henderich; Derick up de Graeff; Francis Daniell Pastorius; and Abraham up Den Graef.3

And it was in fact signed in 1688.

There’s just one problem.

It wasn’t drafted and signed 332 years ago today.

The last part of the Germantown petition states that it is “from our meeting at Germantown, held ye 18 of the 2 month, 1688.”4

Um… that’s not February 18th.

The hitch of course is the fact that a calendar other than the one we use today is what was being used in 1688.

That calendar was the Julian calendar. We didn’t change over to the Gregorian calendar — the one we use today — in England and colonial America until 1752.5

So … What was the second month of the year 1688?

It was April. Because the Julian calendar year didn’t begin in 1688 on 1 January. It began on 25 March. In other words, the 24th of March was 24 March 1687. The next day was 25 March 1688. Making that distinction clear in our dates is why we often see dates between 1 January and March 24 recorded with double dates: “An example of a date using double dating is 16 February 1696/7. At the time it would be considered 1696 following the old style Julian calendar or 1697 following the new style Gregorian calendar.” 6

There’s a really good explanation of the Julian calendar dating and particularly its use in Quaker records on the website of the Connecticut State Library. It explains, in part:

Because the year began in March, records referring to the “first month” pertain to March; to the second month pertain to April, etc., so that “the 19th of the 12th month” would be February 19. In fact, in Latin, September means seventh month, October means eighth month, November means ninth month, and December means tenth month. Use of numbers, rather than names, of months was especially prevalent in Quaker records.7

So as genealogists and family historians, we absolutely can and should study the Germantown Petition and its powerful words beginning a fight against enslavement from the very earliest times of the colonization of America.

But we need to do it on the right day.

Dating history means we celebrate that document on the 18th of April — the “18 of the 2 month” in 1688.

Image: Screencapture from Wikimedia Commons, The 1688 Germantown Quaker petition against slavery.jpg

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Dating history,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 18 Feb 2020).

SOURCES

- See e.g. On This Day, “February 18 : Today’s Historical Events” (https://www.onthisday.com/ : accessed 18 Feb 2020). Also, “Today in History: February 18,” HistoryNet.com (https://www.historynet.com/today-in-history : accessed 18 Feb 2020). ↩

- Germantown Petition, 18 Apr 1688; Haverford College Special Collections; text set out at “Germantown Friends’ protest against slavery 1688,” Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/ : accessed 18 Feb 2020) (emphasis added). ↩

- Ibid. Note that the names are often recorded as Garret Hendericks, Derick op den Graeff, Francis Daniel Pastorious and Abraham op den Graeff. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- And, by the way, we weren’t the laggards: Turkey didn’t switch over until 1926/27. See Konstantin Bikos and Aparna Kher, “Change From Julian to Gregorian Calendar,” TimeandDate.com (https://www.timeanddate.com/ : accessed 18 Feb 2020). ↩

- FamilySearch Research Wiki (https://www.familysearch.org/learn/wiki/), “England Calendar Changes,” rev. 25 Dec 2015. ↩

- “Colonial Records & Topics: The 1752 Calendar Change,” Library Guides, Connecticut State Library (http://libguides.ctstatelibrary.org/ : accessed 18 Feb 2020). ↩

Wonderful and appropriate reminder!

It’s such a great vehicle for an object lesson… in two very different ways…

So under the old calendar, would March 1-24 be the 13th month?

It’s actually a bit more complicated that that. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_calendar#Table_of_months

Thanks, and sorry I wasn’t clear. I was referring to the Quaker practice, in which the word March would not be used. This site gives the answer to my question. Scroll down to the heading “Double Dating.”

https://www.swarthmore.edu/friends-historical-library/quaker-calendar

Evidently all of March was the 1st month, but days 1-24 of the first month (under the old calendar) came after the 12th month. You are correct — it’s complicated!

Oh, and apologies for my off-topic question. This is an amazing post and a document that needs to get much more attention than it does. Thanks!

It’s not off-topic… and yep, it’s complicated!!! 🙂

Sad thing is that slavery still exists in this day and time. Man’s inhumanities to man/woman, will it ever cease?

Oh, this is a good post! thank you!

We need to remember who could write their name in 1688. FD Pastorius was their political leader and in some Niepoth writings Abraham Op De Graaf is identified as a Reformed lay leader or following to some extent the teachings of Menno. The meeting is supposed to have happened in the house of Thomas Kunders, yet he did not sign. There were probably other men of the Original-13 who felt similarly. My emigrant Pieter Keurlis, lived next door, and owned the tavern. He could not write his name. The petition provides insight into the beliefs of those emigrants who arrived 6 October 1683 and established a town for themselves a few miles north of the caves on the banks of the Delaware.