Always always doublecheck

Everything about the entries in the Family Bible says they should be believed.

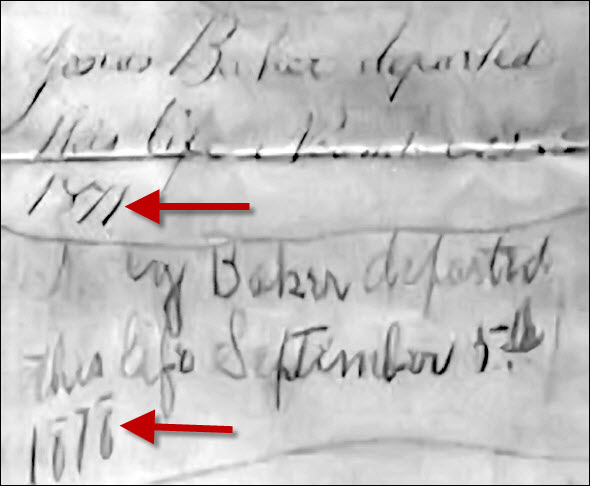

Those two final deaths entered on the family pages were written in two different inks and two different handwritings — or at least by one person at two very different times.

They were entered well after the publication date of the Bible.

As far as the family knows, the Bible was in the possession of a daughter of the couple whose deaths were recorded at the time those entries were made.

So why in the world would anybody go to court records to verify the date of death?

Who would know better than a loving family member carefully entering the deaths of parents into the Family Bible?

The date of death of Josias Baker of Ellis County, Texas, was entered in the Family Bible as 22 November 1871. The date of death of Nancy (Parks) Baker was entered as 5 September 1878.1 The family reports that the Bible was owned by Barsheba Matilda (Baker) Strong Porter, daughter of Josias and Nancy, and it was then lovingly passed down through the family.

It’s the kind of source we love as genealogists — it sure appears to be primary information in an original source providing direct evidence of facts of genealogical importance. Primary because it would have been written by a person with first-hand knowledge; original because it was recorded at the time and not recopied by someone else later; direct because it completely answers the question of when Josias and Nancy died.

Except for two little details.

Josias Baker didn’t die in 1871.

And Nancy (Parks) Baker didn’t die in 1878.

The years of death in both cases in the Bible entries are wrong.

And looking at the court records will tell us the Bible entries have to be wrong.

In an application to the Ellis County District Court, Probate Side, for letters of administration on Josias Baker’s estate, his son-in-law Josiah Porter said “Josias Baker departed this life on the 20th of November 1870.” 1870 — not 1871. Now it’s entirely possible that Josiah Porter could have been wrong and the Bible right — except for one more little detail. The application was filed 7 December 1870.2

Um… nobody gets letters of administration on an estate for somebody who isn’t dead yet.

And in the probate file for Nancy Baker in next-door Dallas County, Texas, her date of death is set out as 6 September 1879 –not 1878. It’s in an affidavit of subscribing witness R.S. Gray dated January 1880 and another by subscribing witness J.R. Claycomb dated January 1880 and in a verification filed by son-in-law Josiah Porter in May 1880.3

They’re unlikely to be wrong about an event that took place only a few months earlier, especially since Nancy was a substantial landowner and there was good reason to get her estate probated quickly. There’s no reason whatsoever why they’d have waited more than a year and then fibbed about the date of death.

And if you’d like a tie-breaker between the Bible and the court records, you can take a look at the tombstones for both Josias and Nancy at the Shiloh Cemetery in Ellis County, Texas. Josias’s stone clearly says that he died in 1870. Not 1871.4 And Nancy’s clearly gives her date of death as 1879, not 1878.5

No matter what the source is, no matter how good we think it is, it’s always a “trust but verify” situation.

And court records are a great place to begin that verification.

Because even that wonderful first-hand original record can be wrong.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “The courts versus the Family Bible,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 21 Feb 2019).

SOURCES

- Baker family Bible record, 1787–1878; The Holy Bible (Philadelphia: Jesper Harding, 1846), deaths columns; Bible Records Collection; Dallas Public Library, Dallas, Texas. ↩

- Ellis County, Texas, probate case packet no. 330, “Jonas” Baker (1870), application of Josiah Porter for letters of administration, undated, filed 7 December 1870; digital images, “Probate records, 1850-1941,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 21 Feb 2019). ↩

- Dallas County, Texas, probate cases, miscellaneous probate packet no. 769, Nancy Baker (1879); County Court, Dallas; digital images, “Probate records, 1850-1941,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 21 Feb 2019). ↩

- Shiloh Cemetery, Ellis County, Texas, Josias Baker marker, memorial 31306643 ; digital image, Find A Grave (https://findagrave.com : accessed 21 Feb 2019). ↩

- Ibid., Nancy Parks Baker, memorial 31306644. ↩

*applauding* As usual, Judy, you hit the nail on the head. I’ve been having a heated discussion with some DAR sisters, trying to explain that Bible records…actually any hand written record…can be inaccurate. Not intentionally, mind you, but still inaccurate. Thanks for providing a great example of how this works.

Glad for the serendipitous timing of the post then! 🙂

Great example. ANY record can be wrong.

In searching for my father’s lineage, in my grandfather’s census records, it state that his father was born in Oklahoma. WRONG. He was born in Ohio, LIVING in Oklahoma at the time of the census.

Thanks for this great teaching post — again! Any ideas why these dates might have been “mis-remembered.”

It’s only a guess — but my guess is that the entries were made much later and not by the daughter but a granddaughter or even more distant relative.

“Um… nobody gets letters of administration on an estate for somebody who isn’t dead yet….”

Um… the story around our local courthouse is that somebody tried to cash in on their inheritance a wee bit early and got caught when the “decedent” turned up in court to contest the probate proceedings, in person and very much alive. After that, the court rules were changed to require a copy of the original death record, certified by the Town Clerk and bearing the Town Clerk’s official embossed seal, to be submitted with the very first petition filed in regard to a decedent’s estate.

(Of course, this may be apocryphal courthouse lore passed along to gullible newly-minted lawyers by old habds among the court clerks, who used to enjoy putting one over on inexperienced newcomers suffering from inflated ideas of their own importance and knowledge of the law.)