Last full measure of devotion

It is Saturday, the 26th of May 2018, here in the United States.

The first day of a three-day holiday that culminates on Monday.

Most of us will try to get out and do something this weekend. In some parts of the country, it’s the start of the beach season. Elsewhere, it might be camping, or a picnic in the park.

But this weekend is for something else, as well.

It’s for remembering.

And honoring those men and women of our families who gave that “last full measure of devotion” and laid down their lives in the cause of American freedom.

In The Legal Genealogist‘s family, that begins with a Virginia soldier who was just 23 years old when he died, that cold December day in 1776.

Unmarried. No descendants.

But not forgotten.

His name was Richard Baker.

He was born 23 December 1753, most likely in Culpeper County, Virginia.1 As far as we’ve been able to determine, he was the 10th of 13 children born to Thomas and Dorothy (Davenport) Baker of Virginia.2

He was born 23 December 1753, most likely in Culpeper County, Virginia.1 As far as we’ve been able to determine, he was the 10th of 13 children born to Thomas and Dorothy (Davenport) Baker of Virginia.2

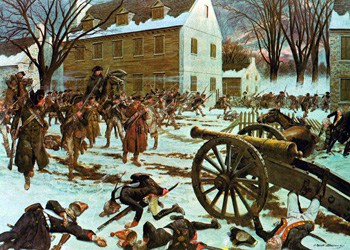

He was serving with his older brother, my fourth great grandfather David Baker, in the 3rd Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line when Washington crossed the Delaware just after dark on Christmas Day 1776. They were headed to what is known today as the Battle of Trenton.

One of Washington’s aides, believed to have been Col. John Fitzgerald, recorded the conditions faced by those troops that day:

It is fearfully cold and raw and a snowstorm setting in. The wind is northeast and beats in the faces of the men. It will be a terrible night for the soldiers who have no shoes. Some of them have tied old rags around their feet; others are barefoot, but I have not heard a man complain. They are ready to suffer any hardship and die rather than give up their liberty.3

Washington wanted to attack just after daybreak but the crossing took longer than expected. By 6:00 A.M., the storm not abating, the conditions were miserable. One commander sent word that the men’s muskets would not fire due to being exposed to the elements. Washington sent word back to rely on the bayonet: “I am resolved to take Trenton.” 4

Washington and his troops succeeded in taking Trenton, and they did so at a small cost to his small force.

But part of that cost was paid by Richard.

There aren’t any details of his death. Just a poignant and quiet statement by his brother David many years later when David applied for a pension:

In a few days after we joined the main army the battle of White Plains was fought. We retreated & recrossed the Deleware The next Battle was at Trenton the 26th of Decemb – I was guarding the Baggage during the battle & had a Brother by the name of Richard killd in that action.5

Little is known or written about casualties among enlisted men at Trenton. Historian David McCullough in his masterful 1776 could document no American troops killed in the fighting, while noting that two men froze to death in the terrible winter conditions.6 Historian David Hackett Fischer contended that Washington’s losses were more, even larger than he knew.7

David Baker’s use of the phrase “killd in that action” rather than saying “he died” to describe his brother’s fate suggests a death in combat, and at least one relatively contemporary account recorded that “Our loss is only two killed and three wounded. Two of the latter are Captain (William) Washington and Lieutenant (James) Monroe, who rushed forward very bravely to seize the cannon.”8 Washington and Monroe were both officers in the 3rd Virginia. Monroe was a lieutenant in the Baker brothers’ own company. If the officers were rushing forward, it stands to reason the enlisted men were too, and a biography of Monroe says they were.9

We’ll never know for certain if that’s how and when Richard fell, but it well may be.

In the end, though, it doesn’t matter.

What matters is that he gave his life for the freedom that all of his kin — and all of us Americans — enjoy today.

And today, at the start of this Memorial Day Weekend, we express our thanks.

To Richard.

And to all who have given their all that we might live free.

SOURCES

Image: Hugh Charles McBarron, Jr., “Battle of Trenton,” via Wikimedia Commons

- John Scott Davenport, “Five-Generations Identified from the Pamunkey Family Patriarch, Namely Davis Davenport of King William County,” PDF, p. 27, in The Pamunkey Davenport Papers: The Saga of the Virginia Davenports Who Had Their Beginnings in or near Pamunkey Neck, CD-ROM (Charles Town, W.Va.: Pamunkey Davenport Family Association, 2009). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- George F. Scheer and Hugh F. Rankin, Rebels & Redcoats: The American Revolution Through the Eyes of Those Who Fought and Lived It (1957; reprint, New York : Da Capo Press, 1987), 211. ↩

- Alan Axelrod, Profiles in Audacity: Great Decisions And How They Were Made (New York : Sterling Pub. Co., 2006), 218-219. See also Kevin Wright, “The Crossing and Battle at Trenton – 1776,” Bergen County Historical Society (http://www.bergencountyhistory.org : accessed 25 May 2018). ↩

- Affidavit of Soldier, 26 September 1832; Dorothy Baker, widow’s pension application no. W.1802, for service of David Baker (Corp., Capt. Thornton’s Co., 3rd Va. Reg.); Revolutionary War Pensions and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, microfilm publication M804, 2670 rolls (Washington, D.C. : National Archives and Records Service, 1974); digital images, Fold3 (http://www.Fold3.com : accessed 28 Apr 2012), David Baker file, p. 4. ↩

- David McCullough, 1776 (New York : Simon & Schuster, 2005), 281. ↩

- David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (New York : Oxford University Press, 2004) 254. ↩

- George F. Scheer and Hugh F. Rankin, Rebels & Redcoats: The American Revolution Through the Eyes of Those Who Fought and Lived It (1957; reprint, New York : Da Capo Press, 1987), 213. ↩

- See Harry Ammon, James Monroe: The Quest for National Identity (Charlottesville, Va. : Univ. of Virginia Press, 1990), 7-8, 13 (the officers “led the company in a charge”). ↩

Thank you for sharing this. I’m also a descendant of David Baker, and had wondered about Richard when I read David’s pension file.

Well, hello there, cousin! My line is David -> Martin -> Martha Louisa m. George Cottrell -> M.G. -> Clay -> Hazel, my mother.

Hey there, cousin! My line is David > Thomas > Nancy md. Hodge Raburn Garland > Lydia, md. John Yelton > Axie md. Wm M. Garland > Charles > Tom, my father

What an unimaginable time that was.

I’m a veteran, and I’m often asked about the difference between Memorial Day and Veterans’ Day. Thanks for helping to point out the distinction. During this weekend, when we all run to the beach and celebrate with BBQ, it’s nice to focus on the true meaning of the holiday. Thank you for sharing the story of your relative and of his sacrifice for our country – heck, for the foundation of our country! It’s good to keep this in perspective while watching war movies this weekend. I, personally, will reflect on my family member – who made his sacrifice during the Korean Conflict.

Tell his story — make sure others know it — help him never to be forgotten.

There’s no way of knowing, but if Richard Baker Was among the men who seized that cannon with James Monroe, his actions may have saved the life of my 3xggrandmother’s brother, who was also at Trenton that night. He survived the war to return home and raise a large family of children who went on to raise families of their own. So thank you for allowing all of us to know about Richard.

I’d also like to recommend this article to anyone who wants to truly understand the price so many ordinary men like Richard paid for our nation’s independence, and the precious rights guaranteed to each of us, personally, in the Bill of Rights. Draw inspiration from their courage, but most of all, never forget.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/grisly-history-brooklyns-revolutionary-war-martyrs-180962508/

My 7x great grandfather survived the Jersey. There is a statement made to the effect that his health was never the same after that. He died c. 1800 almost certainly as a result of his time on the Jersey.

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2018/05/friday-fossicking-june-1st-2018.html

Thank you, Chris

Apologies, error in initial link.. I have included your blog in INTERESTNG BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

http://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2018/06/friday-fossicking-june-1st-2018.html

Thank you, Chris