The case of the collision

The Legal Genealogist is familiar, as we all are, with the phrase about two ships passing in the night. The notion is that, in the darkness out at sea, two ships can pass even fairly close to each other and never be aware of the other.

And, the fact is, that ships are supposed to pass in the night — or, in this case, in the afternoon. They’re not supposed to collide. And when they do, they’re likely to end up in court.

And, the fact is, that ships are supposed to pass in the night — or, in this case, in the afternoon. They’re not supposed to collide. And when they do, they’re likely to end up in court.

Case in point: a ship called the SS Walter D. Noyes, on which was a man named Clair Vernon Berry. He was a seaman — second mate, in fact, on the SS Walter D. Noyes, and he might have been the second mate on the afternoon of 27 April 1920, when the SS Walter D. Noyes had all-too-close an encounter with the SS Barranca near the Thimble Shoal dredged channel in the lower Chesapeake Bay.

He was also the great grand-uncle of genealogist Glenn Berry — and therein lies the tale.

Glenn wrote yesterday1 that he thought he had tracked Clair into the pages of a federal court case, reported at page 690 of volume 275 of the Federal Reporter.

That’s a reported opinion of what’s called an admiralty case: admiralty being “jurisdiction over maritime causes, both civil and criminal, and marine affairs, commerce and navigation, controversies arising out of acts done upon or relating to the sea, and over questions of prize.”2

The particular controversy “arising out of acts done upon or relating to the sea” in this case was a collision between the SS Walter D. Noyes and the SS Barranca in a dense fog. It was described in the evidence on behalf of the SS Barranca this way:

Both the pilot and the master of the Barranca testify that it was not until the steamer was about midway the channel, and three or four minutes after passing buoy 7, that the first fog signal from a vessel approaching in the opposite direction — which afterwards turned out to be the Noyes — was heard. The evidence of the master of the Barranca is that between the first signal heard and the collision just three minutes elapsed ; the pilot, that the time between the first signal and the collision was five or six minutes. The vessels at the time were approaching one another at the rate of about a mile in four minutes, so that, if the testimony of the master of the Barranca be correct, the distance between the two vessels when the first signal was heard was three-fourths of a mile, and if the testimony of the pilot be correct the distance was a mile to a mile and a quarter. At the time the first signal was heard the engines of the Barranca were rung down to dead slow (4 to 5 miles), and a minute later, when another signal from the ap proaching vessel was heard, were stopped. A moment later the Noyes was discovered on the Barranca’s port bow, coming out of the fog apparently at full speed.

The collision occurred within a few seconds thereafter, in spite of the fact that both vessels, as soon as the danger was discovered, went full speed astern; the bow of the Barranca striking the starboard side of the Noyes abreast the bridge. The stem of the Barranca was badly twisted to port, the bridge and a good deal of the upper works of the Noyes carried away, and a considerable indentation made at the point of contact.3(

For the SS Walter D. Noyes, the evidence was:

that the fog set in when she arrived about off, or a little below, Thimble Shoal light ; and that thereafter and until the moment of the collision she sounded fog signals every minute. The master, the second officer, and the quartermaster were on the bridge, which was uninclosed and approximately 100 feet from the bow 01 the vessel. Apparently there was no lookout-man on the fo’castle head, and it is admitted that the navigator of the Noyes, although holding a master manner’s license, had failed to obtain a pilot’s license covering the navigation of Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay.

All of the witnesses for the Noyes testify that … practically from the moment of entering the cut channel they heard the fog whistles of the Barranca ; that their ship was on the starboard or right-hand side of the channel, where it should have been, and where the law required it to be, and so continued up to the moment when the Barranca came in sight ; that they first observed the Barranca when … she was then to the south of and about 1,000 feet away from the line of the dredged channel, … in a direction almost at right angles with the channel, and about four points on the Noyes’ starboard bow. The wheel of the Noyes was immediately put to starboard, and her engines put full speed astern in an unsuccessful effort to avoid the collision which occurred immediately thereafter. The vessels separated in the fog…4

It’s a wonderful case for a lot of reasons, including the fact that the court smacked both parties around. It took a swipe at the master of the SS Walter D. Noyes for not having the proper license and for “navigating a heavily laden vessel down a narrow channel, without a proper lookout, in a dense fog, and at full speed.”5 And as for the SS Barranca, the court said that ship’s own evidence showed that “but for the failure … of those in charge of her navigation, the collision would have been avoided.”6

So… you’re the genealogist of the family, and your great grand-uncle may have been the second mate on the bridge of one of those ships. What do you do?

You do what Glenn did. You ask two key questions: (a) how to cite this case; and (b) where to get the rest of the story.

Citation is an issue here because admiralty cases don’t have the usual types of case names we’re accustomed to seeing: say, Smith, plaintiff, versus Jones, defendant. That garden-variety citation was discussed in “Cite that case!” back in 2012.7

Glenn thought to look at the list of cases at the front of the book, and saw that there it was just listed as “Walter D. Noyes, The (D. C. Va.)” and he saw a journal article published in 1922 that called it “Walter D. Noyes, (U.S. Dist. Ct. Va).” And he didn’t think either of those was entirely right.

In fact, the name of the case is, simply, The Walter D. Noyes. That’s the form for many admiralty cases. And if you’re ever not sure just how a case name is cited, try doing an online search in Google Books or some other digitized book service for the citation (here, since it’s in volume 275 of the Federal Reporter starting at page 690, it’s 275 F. 690), looking for the way other courts in other cases refer to the case.

In this case, at Google Books, that search brings up references to this case in a number of other legal volumes, including Corpus Juris Secundum, a legal encyclopedia; an annotated version of the United States Code; and various digests of cases published by legal publishers. And they all reference the case as The Walter D. Noyes, 275 F. 690.

The other part of the citation that needs work is what’s inside the parentheses. Remember, in “Cite that case!,” we mentioned that the parenthetical always includes the year the case was decided and — whenever you can’t tell what court decided the case just by looking at the name of the reporter series — the court that decided it.

Here, while it was decided by the U.S. District Court in Virginia, the fact is that, even in 1921, there was more than one federal district court in Virginia. So we have to be specific and cite it as the Eastern District of Virginia, abbreviated simply “E.D. Va.”

So this case is cited, then, as The Walter D. Noyes, 275 F. 690, 692 (E.D. Va. 1921).

Now for the fun part: where are the records?

All archival federal court records are held by the National Archives in a wide variety of record groups, with RG 21 holding the records of the District Courts of the United States. But they’re not all in one place. They’re spread out in regional repositories depending on geography. And it so happens that the records of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia are held by the National Archives in Philadelphia.

Which, yesterday, told Glenn that the file on The Walter D. Noyes is more than 100 pages of documents and occupies two thirds of a cubic foot of records. Since the Archives branch has a limit of 100 pages when it does the copying, you know what that means, right?

Road trip…

What a find for this family.

And for anyone who had anybody on the SS Walter D. Noyes or the SS Barranca on that April afternoon in 1920.

When the ships didn’t pass in the night…

SOURCES

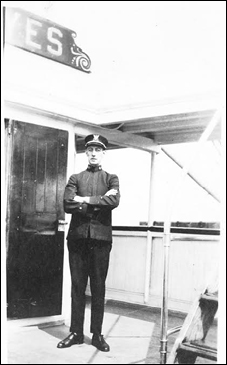

Image: Clair Vernon Berry, believed to be aboard the SS Walter D. Noyes, furnished by Glenn Berry.

- It was actually Monday, but my internet connection was flaky all day yesterday and prevented this blog post from being posted, darn it! ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 40, “admiralty.” ↩

- The Walter D. Noyes, 275 F. 690, 692 (E.D. Va. 1921). ↩

- Ibid., 275 F. at 693-694. ↩

- Ibid. at 694. ↩

- Ibid. at 694-695. ↩

- Judy G. Russell, “Cite that case!,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 19 Sep 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 17 Nov 2015). ↩

Lucky me that my steamboat captain/owner ancestor’s steamboat was in a collision on the Mississippi River, spawning a case on state vs. federal laws on rivers. I went back and reread the materials after taking your course last year and found that I understood it better than I had previously.

That’s neat, Liz! I hope you got the case file on that collision too!

I haven’t been able to locate the original case file yet; any tips would be welcome. Chicago NARA holds the court’s cases but they weren’t able to locate it based on the case name.

And the case is …? (I’m assuming Halderman v. Beckwith, but you know what I say about assumptions…)

🙂 Yes, Halderman et al. vs. Beckwith et al. Thanks for any ideas!

Try giving the Archives this description of the case to see if it helps locate it:

HALDERMAN et al. v. BECKWITH et al.

Case No. 5,907

Circuit Court, D. Ohio

11 F. Cas. 172; 4 Mc Lean 286

July, 1847, Term

Thanks, Judy. I did include “Case No. 5,907” in my request but they said that that wasn’t useful.

The only other thing I can think of is… try again. Seriously, if the request goes to a different person, you may get a different result.

Judy, thanks for the tip about searching the digitized book services (Google Books, HathiTrust, etc.) to see how a case might be cited!

Glad it’s useful, Betsy!