The laws of Alaska

As The Legal Genealogist prepares for the Federation of Genealogical Society cruise to Alaska starting later this week, it’s clear that folks with roots in Alaska sometimes think that there are some amazingly strong parallels between the laws of Oregon and their own laws there in the Last Frontier.

Every time you look at, say, one of the early laws of Alaska as to justices of the peace, you might think that it seems to be identical or very nearly identical to the law in effect on the same such in Oregon.

Every time you look at, say, one of the early laws of Alaska as to justices of the peace, you might think that it seems to be identical or very nearly identical to the law in effect on the same such in Oregon.

And you’d be right.

Start with the fact that there wasn’t any American law governing Alaska of any kind before 1867. That’s when the United States bought Alaska from Russia for the grand sum of $7.2 million.1

At that point, Alaska became American territory — and essentially lawless.

Oh, the act of 27 July 1868 purported to extend some of the laws of the United States to the newly-acquired land — but only “the laws … relating to customs, commerce and navigation.”2

There was, then, no land law — no way to obtain legal title to land. No probate law, and no probate courts. “In short, there was neither civil nor criminal jurisdiction in any part of Alaska. Even murder might be committed, and there was no redress within that colony.”3

It wasn’t until 1884 that a general legal system was imposed in Alaska, by what’s called the 1884 Organic Act: “An Act providing a civil government for Alaska.”4 For the first time, there was to be a governor with authority to see that laws were enforced, a district court with civil and criminal jurisdiction, a clerk to record deeds, mortgages and mining claims — and, in a most unusual provision — a set of laws imposed on the territory:

the general laws of the State of Oregon now in force are hereby declared to be the law in said district, so far as the same may be applicable and not in conflict with the provisions of this act or the laws of the United States…5

Oregon.

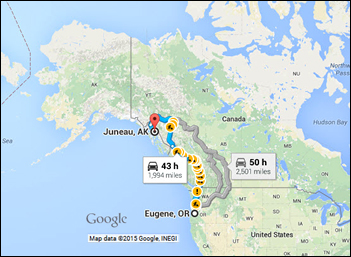

Even today, two days by fast car away from Alaska and its capital.

Oregon.

There’s no definitive source explaining why Oregon law was chosen, rather than the law of any other jurisdiction. One source suggests that several aides of the then Secretary of the Treasury recommended that some of the laws of Oregon be adopted simply to avoid the expense of developing a new code for the new territory.6

Whatever the justification, Oregon law became the law of Alaska. But any changes adopted by Oregon weren’t included. And Alaska law continued to develop after 1884.

First came the Alaska Criminal Code, adopted by Congress 3 March 1899.7 A civil code followed in 1900.8

It was not until 1912 that Alaska was actually given some degree of self-government. In the second Organic Act, which became law 113 years ago yesterday, Alaska was finally given the status of a territory, with its capital at Juneau and the right to establish a territorial legislature.9

And, of course, it was not until 1959 that Alaska became a state, with all of the rights of self-government attached to statehood.10

With remnants, still, of early Oregon law…

SOURCES

- See Judy G. Russell, “Ceded territory,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 19 Aug 2015 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 24 Aug 2015). ↩

- §1, “An Act to extend the Laws of the United States relating to Customs, Commerce and Navigation over the Territory ceded to the United States by Russia, to establish a Collection District therein, and for other Purposes,” 15 Stat. 240 (1868). ↩

- Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of Alaska, 1730-1885 (San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft & Co., 1886), 603-605; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 24 Aug 2015). ↩

- “An Act providing a civil government for Alaska,” 23 Stat. 24 (17 May 1884). ↩

- Ibid., §7. ↩

- Claus M. Naske & Herman E. Slotnick, Alaska: A History, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011), 115. ↩

- “An Act To define and punish crimes in the District of Alaska and to provide a code of criminal procedure for said district,” 30 Stat. 1253 (3 Mar 1899). ↩

- Act Making further provision for a civil government for Alaska, and for other purposes, 31 Stat. 321 (6 June 1900). ↩

- “An Act To create a legislative assembly in the Territory of Alaska, to confer legislative power thereon, and for other purposes,” 37 Stat. 512 (24 Aug 1912). ↩

- “An Act To provide for the admission of the State of Alaska into the Union,” 72 Stat. 339 (7 July 1958), effective 3 Jan 1959. ↩

What had been Washington Territory was admitted as the 42nd state in 1889. In 1884, Oregon was the nearest state. Washington had composed a “Washington State” Constitution in 1878, but it wasn’t officially adopted, so it looks as if the nearest state with an official set of laws available to adopt was Oregon.

That’s as good an explanation as any, but again there’s no documentation for any explanation of why!

Having been born and raised in Alaska and being a resident of Washington for most of my life, I will venture a guess that Oregon was chosen because it was the closest state (Washington did not become a state until November 11, 1889).

That’s most likely the case, Miriam — but there’s no specific evidence for it.

Walter Borneman’s “Alaska: Saga of a Bold Land,” 2003, is the best-documented book I’ve found so far on the pre-history and history of Alaska. He claims that after the purchase from the Russians in 1867 what is now Alaska was officially governed by first the US Army, and then the Navy, with considerable assist from missionaries, who divided up the huge area among them, taking responsibility not just for religious affairs but for education. Pres. Benjamin Harrison’s Organic Act of 1884 called Alaska a “district,” not a “territory,” because the latter would have implied Alaska was headed toward statehood. Neither Harrison nor Congress had any intention of statehood, because of the small population. The Organic Act also did not provide citizenship to the Native Americans, made no provision for law enforcement, and forbade a legislature. Borneman doesn’t speak to the issue of land law, at least not in the section on the Organic Act of 1884. So while the Act stated that the laws were those of Oregon Territory, they were definitely not a carbon copy. This is from pgs. 102-130.

At that point, Washington Territory went from the Pacific to the Continental Divide, taking in what are now the states of Idaho, part of Montana, and some of Nevada, and Wyoming, if memory serves. Its population was, like that of Alaska, minimal, except for Vancouver, across the Columbia River from Portland, Oregon, Walla Walla, in Eastern Washington, and the growing Puget Sound cities of Seattle and Tacoma. Washington Territory still followed the laws of Oregon Territory, more or less, though it wasn’t long–1889–before it attained statehood. I too would assume that the lack of statehood for Washington is the reason Oregon was used as the model.

The other thing Borneman states is that Congress wanted to get things organized in a hurry (some things never change) so they picked Oregon’s already-existing laws, and the fact that they were the closest to Alaska.

The “getting things organized in a hurry” part is fairly well-documented. The choice of Oregon — not.

Wow, I just read these comments and notice of the lack of understanding as to what happened.

On 17 December 1883, the United States Supreme Court on a 9-0 ruling issued its findings for the case EX PARTE CROW DOG. That caused many concerns for U. S. Senator Benj. Harrison, Chairman of the Senate Committee of Territories as to how the US Government could lawfully rule Alaska and the enforcement of law on five Arctic islands to the North of Siberia annexed by the United States Government between June 2 – August 12, 1881.

Why Oregon Law, one issue at the December 17, 1883 meeting between Senator Harrison and Major Ezra W. Clark, Jr. was how these three laws would apply to Alaska, viz., Law Oregon 1872, p. 129

Law Oregon 1874, p. 76

Law Oregon 1878, p. 42.

Ezra W. Clark, ESQ. was the attorney for the Alaska Board at the United States Department of the Treasury.

He drafted the bill they became the

Harrison Alaska Organic Act. Harrison introduced that bill on December 18, 1883. In was signed into law on May 17, 1884, by President Chester Arthur with Ezra W. Clark, Jr. present.

Major Clark received a Waterman Fountain Pen from President Chester Arthur at his signing of the Harrison Alaska Organic Act.

After that signing Major Clark walked to the Treasury Department and held a meeting of the Alaska Board which declared six islands as “known as Alaska”, viz., Bennett, Forrester, Henrietta, Herald, Jeannette, and Wrangell (annexed by the United States Government on 12 August 1881 under the name “New Columbia Land” by 3rd Lt. William Edward Reynolds USRM).

Henrietta, Herald, and Jeannette islands were annexed by George Wallace Melville for the United States

Government at Cape Melville between June 2-3, 1881 under the group name “Jeannette Islands” after his ship the USS Jeannette.

Bennett Island was annexed for the United States Government on July 29, 1881 by George Washington DeLong USN.

Forrester Island of the San Carlos Islands In the North Pacific Ocean was to the South of Alaska because it was not included in the 1799 claim of Tzar Paul I and was in dispute between the Russian and United States governments since year 1836.

Harrison wanted that dispute to end.