A win for the Irish tenant farmer

Reader Robert Kirk is closing in on Samuel Kirk of County Cavan, Ireland, as a possible second great grandfather.

And in gathering information about the man, he came across a news report of a lawsuit in which Samuel Kirk was involved, and wasn’t sure just what the case was all about.

And in gathering information about the man, he came across a news report of a lawsuit in which Samuel Kirk was involved, and wasn’t sure just what the case was all about.

“A possible(?) ancestor of mine is accused of dilapidation,” he wrote. “Ever hear of that crime or tort? … I’m guessing it’s a landlord-tenant damage claim of some sort.”

And Bob has it exactly right. It is a landlord-tenant case for damages.

Here’s what the article reports:

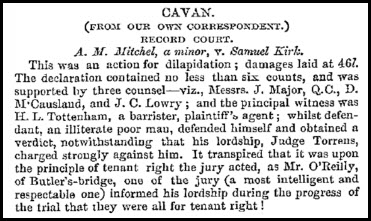

This was an action for dilapidation; damages laid at 46£. The declaration contained no less than six counts, and was supported by three counsel–viz., Messrs. J. Major, Q.C., D. M’Causland, and J.C. Lowry; and the principal witness was H.L. Tottenham, a barrister, plaintiff’s agent; whilst defendant, an illiterate poor man, defended himself and obtained a verdict, notwithstanding that his lordship, Judge Torrens, charged strongly against him. It transpired that it was upon the principle of tenant right the jury acted, as Mr. O’Reilly, of Butler’s-bridge, one of the jury (a most intelligent and respectable one) informed his lordship during the process of the trial that they were all for tenant right!1

So… first question: what’s dilapidation?

The term is used, Black’s Law Dictionary reports, “in the law of landlord and tenant, to signify the neglect of necessary repairs to a building, or suffering it to fall into a state of decay, or the pulling down of the building or any part of it.”2

And in his dictionary, Bouvier says: “Literally, this signifies the injury done to a building by taking stones from it; but in its figurative, which is also its technical sense, it means the waste committed or permitted upon a building.”3

So this wasn’t a crime — this was a civil action seeking money damages, brought by a landlord against a tenant for damages or decay of any building on the rented property.

What it also was, at that particular time and place, was a small skirmish on a much broader battlefield between the Irish and the English, and between the large landowners and the huge tenant class in Ireland. And that comes through clearly in the reference in the article to the jury’s support for tenant right.

Ireland at this time was undergoing a massive upheaval. As explained in the description of the Landed Estates Court records set at findmypast:

By the mid 19th Century many of the large Irish estates were in serious financial difficulty. Land owners found themselves legally obliged to pay out annuities and charges on their land, mainly to pay mortgages or ‘portions’ to family members contracted by marriage settlements and/or wills of previous generations. All of these payments had to be met, before the owner/ occupier could take an income from their estate.

By the time of the Famine, as prices for sale or rental of land plummeted, the monies that had to be paid out from the individual estates remained the same, and many Irish estates became insolvent as debts exceeded earnings. However, the landowners could not sell their estates to discharge their debts, because the land was entailed. In 1848 and 1849, two Encumbered Estates Acts were passed to facilitate sale of these estates. Under the second act, (12 & 13 Vict., c. 77), an Encumbered Estates Court was established, whereby the state took ownership of these properties and then sold them on with a parliamentary title, free from the threat of contested ownership.4

These financial crises of the landowners had them squeezing their tenants, and one major area of disagreement between the landowner and the tenant was responsibility for upkeep and improvements on the tenant property. The landlords wanted the tenants to be responsible for all of the upkeep and improvements and, as here, tried to sue to dilapidation when the tenant didn’t do everything needed.

The tenants, on the other hand, were strongly of the view that maintenance and improvement of the property and its buildings was the responsibility of the landowner. And in 1850, the Tenant Right League was formed in Ireland to fight for a better deal for the Irish tenants.5

In the parliamentary elections of 1852, several Tenant Right candidates won on a platform that included this bold proclamation: “Nothing shall be included in the valuation, or be paid under it to the landlord, on account of improvements made by the tenant in possession, or those under whom he claims, unless these have been paid for by the landlord in reduced rent, or in some other way.”6

So Samuel Kirk’s jurors were on his side from the outset. As supporters of Tenant Right, they believed it was the landlord’s job — not the tenant’s — to pay for needed improvements and repairs.

The Tenant Right League fell apart in only a few years in the tensions between Northern Irish Presbyterians and Southern Irish Catholics, but in that window of opportunity Samuel Kirk — “an illiterate poor man” — prevailed despite having the judge and three lawyers against him.

Sometimes — if history is on your side — even the little guy can beat the odds.

SOURCES

- (Dublin, Ireland) Freeman’s Journal, 26 July 1851, p.4; digital image provided by Robert Kirk from Irish Newspaper Archives. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 367, “dilapidation.” ↩

- John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America and of the Several States of the American Union, rev. 6th ed. (1856); HTML reprint, The Constitution Society (http://www.constitution.org/bouv/bouvier.htm : accessed 16 Feb 2014), “dilapidation.” ↩

- “Find your ancestors in Landed Estates Court Rentals 1850-1885,” findmypast.ie (http://www.findmypast.ie/ : accessed 16 Feb 2014). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Tenant Right League,” rev. 12 July 2013. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

What a cool discovery your reader, Robert Kirk, made. The tenant farmers were in a bind because before that time if they improved their properties, the landlords raised their rents. If they didn’t, they could be charged with dilapidation. Sometimes the little guy did win. I can imagine that a pint or two were lifted in his honor that day at the local pub!

It’s a wonderful find, and I hope there are some court records still in existence to show exactly what the tenant was charged with doing! (And, of course, I hope Samuel turns out to be Bob’s ancestor!)

Judy, would they be chancery court records, since it is an issue of equity? The chancery court indexes survive for cases prior to 1922, but they might reveal less than in the newspaper article. I’d still take a look, though. The Family History Library has the indexes on microfilm.

I’m not sure these would be chancery court records, Cathi: landlord-tenant claims might be routine common law actions since they’re for money damages. Judge Torrens, the judge who presided, appears in other records I could find in a quick check online as sitting in chancery or as a judge of the assizes (which would make him a judge of the King’s or Queen’s Court). If there’s a Who’s Who biographical record for County Cavan, that should give you the best info on exactly what court(s) Torrens was assigned to.

Judy… Many thanks for your information. I’m closer to thinking this Samuel is my ancestor because our family ‘history’ has a Samuel Kirk from that part of Cavan, of about the right age as our progenitor. But, I’ll have to better narrow him ’cause I’ve been burnt before by relatives who lived in a small area, and kept giving their offspring the same names. Do you know hoe many Robert Millers there were in Longford in the mid 1800s.

Anyway, thanks again and as recompense, here’s an appreciation of the law profession I got from another Irish article…

Anglo-Celt, Friday, November 30, 1849

PROFESSIONAL COURTESY.- At the conclusion of the late Kilkenny sessions the assistant-barrister, Mr. Nicholas PURCELL O’GORMAN, made some strong observations upon the indecorous conduct of the attorneys of his court, “who did nothing,” he said, “but sneer at him, and endeavour to cast ridicule upon him. But I’ll bear it no longer,” exclaimed the enraged judge, “as this very night I shall write off and insist upon being transferred to another county.” “Does your worship think,” said Mr. Michael HYLAND, solicitor, addressing himself to the irate law dispenser, “that a memorial signed by all the attorneys of the court, backing your application, would be of any assistance in obtaining your object?” A look of peculiar ferocity was the only response to the generous interrogatory.

Glad to help, Bob, and good luck in nailing down your ancestor… and I LOVE the Anglo-Celt piece!