A study in contrasts

It’s a great question, from reader Dana J.:

Does contract law override “fair use”? Can a website’s terms of use prohibit users from using the copyright-protected works under fair use? It seems that copyright’s fair use provision might be one of the only times you could violate a website’s terms of use if the work is being used for commenting, news reporting, scholarship, and other fair use applications.

And it’s one that anyone who — like The Legal Genealogist or genealogists and researchers anywhere — would love to see a resounding yes answer to: yes, we can use the fair use provision to violate terms of use.

Which, of course, means that the answer is…

No.

Sigh…

Let’s back up for a minute and make sure we’re all on the same page as to what we’re talking about here.

Terms of use (or terms of service or terms and conditions — whatever they’re called) are the limits somebody who owns something you want to see or copy or use puts on whether or not he’ll let you see or copy or use it. These are limits that are different from copyright protection, since the law says what is and isn’t copyrighted and you can own a thing without owning the copyright. So this isn’t copyright law; it’s contract law — you and whoever owns the thing you want to see or copy or use reach a deal.

The phrase “terms of use” isn’t defined in legal dictionaries. The closest they come is the definition of “use” by Black to include “the right given to any one to make a gratuitous use of a thing belonging to another.”1 Wikipedia says terms of use, terms of service and terms & conditions are all the same thing (they are) and defines the phrase as “rules by which one must agree to abide in order to use a service.”2 That’s a pretty fair definition.

But, you’re thinking, if it’s rules, how can it be considered a contract? Nobody gave you a choice about the rules when you subscribed to, say, GenealogyBank.com or Ancestry.com, did they?

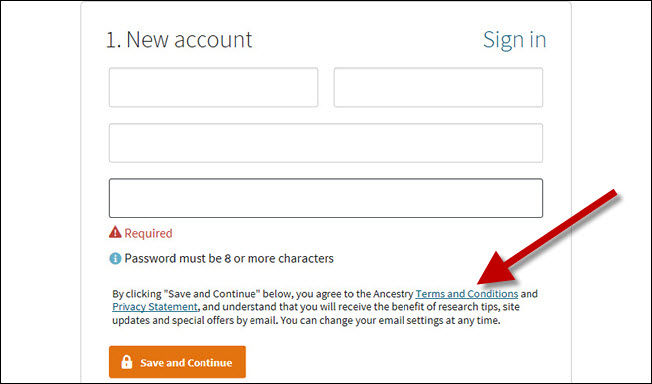

Actually, they did. Exactly the same kind of choice you have in a lot of things in life: take it or leave it. When you created your account with one of the many services we use around the web, commercial and non-commercial, there comes a point in the join-up or subscription process where there’s a button or a check box or something. It always says something like the example shown in the graphic below: if you click on it or check the box, you’ve agreed to be bound by what the terms of use are.

It’s a little like your relationship with the TSA. You don’t have to go through security at the airport. Of course, that means you don’t fly, either.

Copyright, on the other hand, is a set of legal protections “granted by statute to the author or originator of certain literary or artistic productions, whereby he is invested, for a limited period, with the sole and exclusive privilege of multiplying copies of the same and publishing and selling them.”3 Or, in the words of the U.S. Copyright Office, “a form of protection provided by the laws of the United States to the authors of ‘original works of authorship’ that are fixed in a tangible form of expression” consisting of the exclusive right to, among other things, make or distribute copies of the work or authorize others to do so.4

Copyright is automatic. It comes into existence the minute the work is created and persists as long as the law specifies (at the moment, the lifetime of the author plus 70 years].5 And, under the law, it has certain exceptions including the one Dana raises, the concept called fair use.

That, according to the Copyright Office, is “a legal doctrine that promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances. Section 107 of the Copyright Act provides the statutory framework for determining whether something is a fair use and identifies certain types of uses—such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research—as examples of activities that may qualify as fair use.”6

So fair use can be a way for us to use copyright-protected works for teaching, scholarship and research — the kinds of things we do as genealogists.

Except…

Except when we agree not to.

And that’s where contracts like the ones in terms of use come into play.

By contract, the agreement between us and a website for example, we can give up any number of rights we might otherwise have — like the right to sue in court rather than arbitrate a dispute — in return for something we want to have — like quick and easy online access to information.

It’s the fact that both sides get something (the website, our money; us as users, online access to information or data or records) that makes the contract enforceable. So when we enter into an agreement with a website with terms of use that say we can’t use something in a particular way, that contract is generally honored by the courts.

And that’s why, as a general rule, a website’s terms of use can prohibit users from using the fair use doctrine to use copyright-protected works the website serves up.

Not because copyright law says we can’t use them.

But because we agreed we can’t use them, when we clicked that box, and accepted the website’s terms of use.

SOURCES

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 1204, “Use.” ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Terms of service,” rev. 13 Feb 2018. ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 276, “copyright.” ↩

- U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 1: Copyright Basics, PDF, 1-2 (https://www.copyright.gov/ : accessed 4 Apr 2018). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- U.S. Copyright Office, “More Information on Fair Use,” (https://www.copyright.gov/ : accessed 4 Apr 2018). ↩

I appreciate your information. I wondered if anything came of a lawsuit against you regarding the use of photographs. I had started purchasing old photos of people who are identified so I could make digital copies and offer to people (minimal fee) for their research. (Following up with my own genealogy research to verify people.) It is something I know I would appreciate for my own family tree. But now I am concerned I won’t be able to do this. What are we supposed to do in instances of a photograph that is really old, but doesn’t have a photographer listed? Would really appreciate your insight. I am not looking to make a bunch of money. Just wanted enough to cover the cost of purchasing a photo and taking the time to make quality digital copies.

First off, I’m not sure who you’re responding to since I’ve never been sued because of use of photos. Second, you’re asking for legal advice about a current legal question and for that you need to consult with an attorney licensed to practice in your jurisdiction.