Annotating the names on the maps

In the spring of 1862, the city of Corinth, Mississippi, became a flashpoint in the U.S. Civil War between troops under the command of Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard and Union forces under the command of Major General Henry Halleck.

Located at the intersection of two key rail lines, the city’s strategic value was clearly recognized by both sides. Halleck called Corinth and Richmond, Virginia, “the greatest strategic points of the war, and our success at these points should be insured at all hazards.” Beauregard told his superiors: ““If defeated here we will lose the Mississippi Valley and probably our cause . . . (and) our independence.”1

The attacking forces began their siege of the city at the end of April 1862. The city fell to Union control when Confederate forces retreated on 30 May 1862. It was a critical event in the war: “Most historians believe that the Union seizure of the strategic railroad crossover at Corinth led directly to the fall of Fort Pillow on the Mississippi, the loss of much of Middle and West Tennessee, the surrender of Memphis, and the opening of the lower Mississippi River to Federal gunboats as far south as Vicksburg. And no Confederate train ever again carried men and supplies from Chattanooga to Memphis.”2

So… you’re a Union commander in 1862. This is your goal.

What tool is going to be the single most important thing you can have?

The Legal Genealogist submits that the right answer to that question is… a map.

Halleck needed to know where everything was.

He also needed to know who everyone was who might be in his way.

And therein lies the tale for us as genealogical researchers here nearly 160 years later.

Because so many of the maps that have ever been drawn — including the one prepared by a Union architect-turned-engineer/mapmaker named Otto H. Matz of “the country between Monterey, Tenn: & Corinth, Miss: showing the lines of entrenchments made & the routes followed by the U.S. forces under the command of Maj. Genl. Halleck, U.S. Army, in their advance upon Corinth in May 1862”3 — show the names and locations of residents and business or property owners.

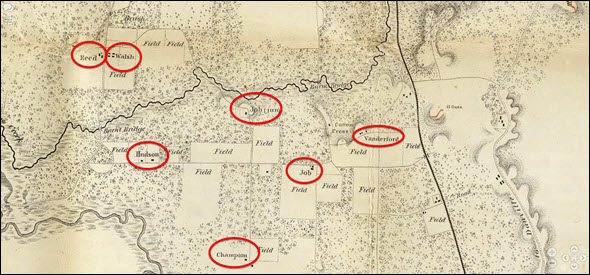

Here, for example, is just one part of that particular Matz map from 1862, and the circles show the names and locations of the homes of seven separate property owners: Reed; Walsh; Hudson; Champion; Job; Job Junior; and Vanderford.

Think we might want that if we’re descended from the Reed, Walsh, Hudson, Champion, Job or Vanderford families?

Now… how are we ever going to find their names on that map?

That’s always been the problem. Even if we know that maps like that were created during the Civil War, how can we possibly begin to search for the specific entries we might be interested in? And this isn’t at all limited to Civil War-era maps. Lots of maps from all time periods have property owners identified, and businesses, and churches, and more.

And that particular problem — finding information like that buried in the maps — is what the fabulous David Rumsey Map Collection hopes to address through a new collaboration with Machines Reading Maps (MRM). In a one-year project funded by David Rumsey himself, the MRM teams (including researchers at The Alan Turing Institute, the University of Minnesota, and the Austrian Institute of Technology) will be able to test and expand their map-reading tools and methods with the Rumsey collection of 60,000 digitized historical maps to try to provide just that level of information to end users.

The email announcement from MRM and the David Rumsey Map Collection explained:

This research will make the Rumsey Map Collection the first large digitised map collection in the world to be fully searchable via text. For all the place names, we will also infer the semantic types and the links to external knowledge bases like Wikidata. This will make countless features that did not previously appear in the map’s metadata, finally visible and discoverable. At the same time, the enrichment of the maps will enable, for the first time, complex searches across different map series, like finding saloons in nineteenth-century California or all the businesses found within 2 miles of British railway stations.

Building on top of the ongoing work on collections held at the National Library of Scotland, British Library and Library of Congress, and supported by AHRC and NEH funding, this new collaboration will enable MRM to process a large corpus of georeferenced maps (around 60,000 documents) in the David Rumsey collection with the computer-vision-based machine learning model mapKurator. mapKurator detects and recognises the text on maps, in a wide variety of scripts and styles, and then links those labels (including only partially recognised ones) to external knowledge bases like OpenStreetMap or WikiData.

The first outcomes will be fine tuned through two processes: one computational and one manual. The first one involves the training of artificial intelligence models using real maps from the Rumsey collection and synthetic ones developed by the project team. For the second, the project will extend LUNA, the Rumsey Collection’s online map viewer, with annotation functionality. Building on a bespoke annotation system developed in MRM, the new annotation interface will make it possible for the public to help validate and improve the annotations produced automatically via mapKurator.

This collaboration with the Rumsey Collection will sharpen MRM tools, making them more flexible in new contexts. In particular, it allows the researchers to explore solutions for dealing with the challenging scale and variety of this unique collection, which features dozens of different languages and cartographic traditions. The MRM and David Rumsey Map Collection teams also look forward to collaborating with a large and diverse community of users, and to making them co-authors of the maps’ enrichment.

This operation will generate an unprecedented amount of free and reusable data, of great historical, geographical, scientific, and anthropological value, as well as precious metadata that will improve the accessibility of the collection, and active engagement with map enthusiasts.4

Oh boy.

I can’t wait to see how this works.

Even if I don’t trace back to the Reed, Walsh, Hudson, Champion, Job or Vanderford families… there are so many others to whom I may well be related… and may soon be able to find.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Rumsey Maps to be text-searchable,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 7 Mar 2022).

SOURCES

- “The Siege and Battle of Corinth: A New Kind of War,” Teaching with Historic Places, National Park Service (https://www.nps.gov/ : accessed 7 Mar 2022). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- O.H. Matz, Map Of The Country Between Monterey, Tenn. & Corinth, Miss., David Rumsey Map Collection (https://www.davidrumsey.com : accessed 7 Mar 2022). ↩

- “New collaboration between Rumsey Map Collection and Machines Reading Maps. mapKurator will scan text in 60,000 georeferenced Rumsey maps. The data generated will make the Rumsey Map Collection the first large digitized map collection in the world to be fully searchable via text,” email announcement, 4 Mar 2022, David Rumsey Map Collection; received and held by author. ↩

I love the David Rumsey maps and have been using that as a favorite resource for many years. This will be a great advancement.

David Rumsey announced an update on 31 May 2023 that this project would be available to the public “in a month,” so maybe late June/early July 2023:

https://twitter.com/DavidRumseyMaps/status/1663785441697624074