Of the four-legged kind…

It’s just a handful of pages of records in a book of town records from Shaftsbury, in Bennington County, Vermont, that FamilySearch has labeled Births, marriages, deaths 1765-1893 vol 1.

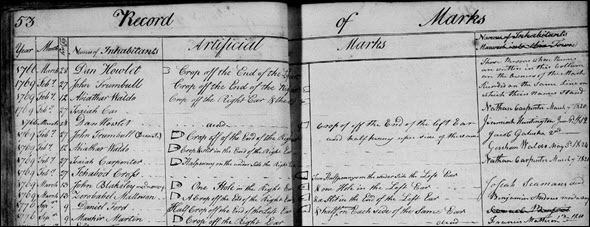

After 24 pages of marriages starting in 1785 and running to 1805, and then a record of births from 1784 through 1834, and before the book picks back up with marriages starting in 1806, up pops this seemingly incongruous set of pages that had reader Alice Dyer Finley puzzled.

They’re labeled as the Record of Marks,1 all the names recorded are of property owners, and Alice hadn’t seen a record like this before.

“Wondering what this is all about,” she wrote.

The Legal Genealogist is happy to oblige.

Because we come across records like these all over the country — though generally not tucked into books of births, marriages and deaths! — and we all ought to be using them a whole lot more than we are.

These are records of the earmarks people used on their livestock. So marks, or earmarks, or brands — whatever they’re called in that area — will all show ownership of animals.

And, as these town records indicate, these records can go way back.

The first of this particular set of town records of marks shows that Dan Howlet recorded his mark — a crop off the end of the left ear — in March of 1766.2 Then came John Trumbull with his brand of a crop off the end of the right ear, recorded 27 February 1769.3

Now… somebody is sitting out there wondering what possible value this record set can have other than to add a lovely line in a family history: “And on the 28th of March 1766, Dan Howlet recorded his livestock mark, a crop off the end of the left ear.”

Ah, but read on. On that same page, four entries down, we get another bit of information about that man — with the same date. It reads “dead.”4 Three others on that first page were also recorded as dead (John Trumbull, Elijah Bottum and Isaac Spencer), and four more (John Blakeley, Daniel Goff, Judah Worden and Bigeloe Lawrence)as “moved away.” 5 So it looks like all of the very earliest records, from 1766-1781, were being re-recorded and updated as of the time when they were entered in this book.

You see it now, don’t you?

First, we nail these people’s feet to the floor when they register the mark. They were there in that town at the time they registered.

Then the town cared enough to record when people died or moved away — thus potentially freeing that mark for use by someone else.

We may not find a deed documenting the person leaving town after selling up the family farm, or a death record particularly in places outside of New England where vital records began to be kept much later. But this will do in a pinch as a substitute, won’t it?

So there’s real genealogical value in these records. And we can often find these records digitized online — use brand, mark, and earmark as good search terms, and check every possible source. FamilySearch (use the catalog!!) is a great resource, but don’t overlook the digitized book services like Google Books, HathiTrust Digital Library and Internet Archive.

And when we do find them, we want to think about everything else a record like this can tell us.

In some jurisdictions, you’ll find different brands or marks being recorded for different kinds of livestock. The record tells a very different story in a county where all the marks or brands are for cattle compared to one where they’re all for sheep or horses.

And a record like this talks to us about the people themselves. In Vermont, registration of brands was voluntary.6 So we know that these townspeople cared enough about protecting their livestock from both being stolen or just straying and being claimed by someone else as strays to take the time to register.

In this particular record set, it also talks to us about William D. Taft, recorded as of 12 October 1868, with the notation: “Marks his Turkeys.”

Brands and marks are great fun. And they tell the stories of what was, in reality, a vital part of our ancestors’ lives.

A very different set of vital records tucked into the pages of a vital records book.

Good find, Alice.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “A different set of vital records,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 8 Mar 2022).

SOURCES

- Town of Shaftsbury, Births, marriages, deaths 1765-1893 vol 1, Record of Marks, pp. 53-62; digital images, Film 005464252, images 55-59, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ : accessed 8 Mar 2022). ↩

- Ibid., entry for Dan Howlet, 28 March 1766, Film 005464252, image 55. ↩

- Ibid., entry for John Trumbull, 27 Feb 1769. ↩

- Ibid., line five. ↩

- Ibid., various entries, 1766-1781. ↩

- See e.g. Chapter XLVII, “Of Marking of Cattle,” 28 February 1797, in The Laws of the State of Vermont, Vol. I (Randolph : Legislature, 1808), 482; digital images, Google Books (https://books.google.com/ : accessed 8 Mar 2022). ↩

Don’t forget that prior to the advent of barbed wire, most cattle were grazing in the open (out west guided/guarded by cowboys, but in the east they’d be on the Common), so it was pretty easy for your cattle and someone else’s to get mixed together. The brands were the only way to claim ownership. Cattle rustlers would have a “running iron” to add more lines to change the brand on an animal. For some of these folks, registering their brand was more important than registering their deed (and, indeed, worth more!).

There’s a system here in the Lake District of NW England where sheep graze on the mountains and are not fenced in; with our traditional breed, the Herdwick, each ewe has her own patch or heaf, inherited from her mother. Traditionally farmers had lug marks (clips from the ear) just as described here; there are handbooks which identify who owns which sheep so that those that stray can be returned. That’s being replaced by ear tags. There are also smit marks, where the animals are marked with coloured dye markings, so that they can be recognised from afar; and here too there are handbooks to enable shepherds to tell which sheep belongs to whom.

So what happens when an animal is sold or traded??? It sounds like these brands or earmarks are intended to be permanent.

A typical way of dealing with it would be to add something to the existing mark (another clip or hole or whatever) and register the new mark.

In Australia, stock marks are often a vital genealogical resource, especially for non-British immigrants. Naturalization was often required before land could be purchased, so they often rented land until they had enough residence time to qualify for naturalization and then land purchase. Meanwhile they almost always had at least one cow, and registered their brand – sometimes the earliest genealogical record they left (as steerage passengers were often unlisted). Some puzzles I had over which family with a common name was mine were solved by examining the stock brands. Rather like coats of arms being similar but differenced, my ancestor siblings often had similar but differenced stock brands. And the stock brand list gave their location too. That all leads to public records of lost or impounded stock which can help build a picture of life.

Often overlooked but sometimes really useful.