Tests and ethics

Reader Andrea and her sister have discovered that their father left at least one other daughter by another relationship. They’d like to know for sure, and wonder what test they should take and what ethical considerations they might want to review in testing, such as who owns the testing samples and whether testing consent should be in writing.

Great questions, one very easy and the others more complex.

Let’s start with the easy question: what test should the sisters take?

They’re thinking one of the autosomal DNA tests should work, and they’re absolutely right. But this will be a slam dunk if they choose one of the testing companies where they can actually see where their DNA does or doesn’t match their possible half-sisters. Because if they are in fact paternal half-sisters, a chromosome browser view of the results will make it abundantly clear.

Here’s why: we all inherit 23 pairs of chromosomes from our parents. One chromosome in each pair comes from our fathers; the other in each pair comes from our mothers. And 45 of those 46 chromosomes will be a blend of chromosomes our parents inherited from their parents, so some from both of our grandfathers and some from both of our grandmothers. It’s that mixing — recombination, in DNA parlance1 — that makes us different even from our full blood siblings.

But the 46th chromosome won’t be a mix at all. It’s in what’s called the sex-determinative pair — and the inheritance pattern there is different.

Males and females both inherit one X chromosome from their mothers that’s a mixture of the DNA of their maternal grandmothers and their grandfathers. But what they inherit from their fathers is very different.

Males inherit a Y chromosome from their fathers, passed down from their father’s father’s father and so forth back through time.2 This chromosome contains nothing mixed in from the grandmother: she had no Y chromosome to mix with the grandfather’s DNA to pass to their son.

Females inherit an X chromosome from their fathers, the exact same chromosome those fathers received from their mothers. Since Dad only has that one X chromosome, there’s nothing for it to mix with before he passes it to his daughters — no recombination can occur. So whatever mix from maternal grandma and grandpa got passed to Dad is what every daughter of that father receives.

And that shows up really well in a chromosome browser that shows the X chromosome, a tool that’s available at 23andMe and Family Tree DNA. And between the two, 23andMe has the better tool for this purpose, since it shows where the bits and pieces of DNA we inherited are fully identical (we got the same bits and pieces from both parents as a match did) and where they are half-identical (we got the same bits and pieces from one parent but not from the other).

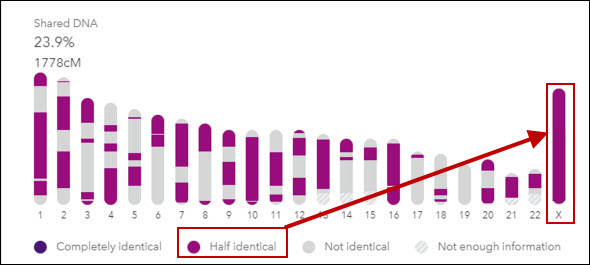

Here’s roughly what paternal half-sisters should look like in the DNA details chart at 23andMe:

Notice the solid match on that X chromosome, and notice that it’s all half-identical — meaning no part of it came from the other parent. Sisters who share both parents will have some areas that are that darker blue for completely identical. So Andrea and her full sister should match each other on that entire chromosome, but with some blue areas since they will both have an identical X from their fathers and some areas they both inherited from their mother. Andrea and her full sister should match any paternal half-sister on that entire chromosome, but only in the purple of half-identical.

So… that’s the easy part. What test? Autosomal, and for this I’d recommend 23andMe, since it makes that half-identical versus fully identical distinction very clear.

On the ethics side… first and foremost, anybody considering doing DNA testing for any reason needs to carefully read the Genetic Genealogy Standards. Developed in 2015 by genealogists, genetic genealogists, and scientists, these remind us that:

• “DNA test results … can reveal misattributed parentage, adoption, health information, previously unknown family members, and errors in well-researched family trees, among other unexpected outcomes.”3

• “DNA tests may have medical implications.”4

• “…[C]omplete anonymity of DNA tests results can never be guaranteed.”5

• “…[O]nce DNA test results are made publicly available, they can be freely accessed, copied, and analyzed by a third party without permission.”6

Put another way, this means that we need to be sure everyone who tests does so after giving informed consent.7 And there’s so much that goes into that decision when it comes to DNA testing. Among the questions are

• Does the tester want someone else to be able to access the results? Or even manage the test?

• If the tester wants someone else to manage the test, does that include downloading the raw data and uploading it elsewhere, to another company’s or service’s database?

• Does the test manager have permission in advance to add on other services or tests that are or become available?

• Who has the right to manage the test and make decisions about it after the tester dies?

It just makes sense to get all of that in writing so there are no misunderstandings and no hard feelings down the road. There are tools to help with this, and I’ve written about those tools before.8

Now… as between the testing company and the testers, it’s crystal clear that the testers own their own DNA samples. They can, if they choose, tell the company to destroy any remaining samples and remove all results from their databases. Even if we pay for another person’s test, it’s that other person who owns the DNA sample. Which is why getting a written signed consent before we go forward can avoid a lot of headaches down the road.

If everyone who tests does so with eyes wide open, and with an in-advance agreement on what can be done with the results, the testing process is fraught with a lot less peril after the results come in.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Finding sisters,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 12 July 2020).

SOURCES

- ISOGG Wiki (https://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Recombination,” rev. 14 Apr 2019. ↩

- Ibid., “Y chromosome DNA tests,” rev. 4 Sep 2019. ↩

- ¶ 12, Genetic Genealogy Standards (https://www.geneticgenealogystandards.com/ : accessed 12 July 2020). ↩

- Ibid., ¶ 10. ↩

- Ibid., ¶ 6. ↩

- Ibid., ¶ 7. ↩

- See ibid., ¶ 2. ↩

- See Judy G. Russell, “Forming consent,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 15 Dec 2019 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 12 July 2020). ↩

Two comments on your excellent summary. You are correct that 23andMe has only half identical SNPs on chrX (as does MyHeritage) but Ancestry also includes pseudo-autosomal chrX SNPs and they behave somewhat differently (see https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/352732v1.full.pdf+html) for a discussion of this). Also, searching for half-siblings as here is much harder than other relatives as that half-sibling has to have done a genetic test themself in order to be found, unlike forensic or unknown relatives with connections from past generations who may be found using other descendants as well.

Thanks for all your helpful posts.

They already have identified the test candidates; they’re not fishing to find them. So their concern is simply how best to show that the candidates are or are not half siblings.