The office of the constable

So The Legal Genealogist is still poking around in Ohio legal resources this week, preparing for this weekend’s spring seminar at the Hamilton County Genealogical Society — and was confronted with a challenge.

One of the treatises I found, and have found very useful, is an 1843 treatise on local officials in Ohio in those early days of Ohio statehood.1

One of the treatises I found, and have found very useful, is an 1843 treatise on local officials in Ohio in those early days of Ohio statehood.1

Written by an Ohio federal judge who had previously served as a justice of the peace, county prosecutor, state representative, state senator, court clerk and U.S. congressman before being nominated to the U.S. District Court by President Andrew Jackson,2 the volume describes the roles of justices of the peace, township trustees, and constables.

Constables.

Not a term we hear an awful lot here in the 21st century, is it? I mean, the office does still exist in some places3 but not too many people deal with constables on a day-to-day basis.

So… what exactly was a constable in Ohio in the 19th century?

According to Ohio law, constables were ministerial officers of the courts held by justices of the peace and had functions in both civil and criminal cases.

On the civil side:

First — They shall have power and authority to execute process of subpoena in civil cases, throughout their respective counties.

Second — And they shall, moreover, execute all such other legal process in civil cases, as may be directed to them by any justice of the peace ; and shall do and perform such other services as may be required by law.

As the ministerial officer of the courts of justices of the peace, it is the duty of a constable to be in attendance on those courts, when in session; to aid the justice in preserving order and decorum, in such courts, and generally, to obey all legal orders issuing from a justice, having reference to this object.4

And over on the criminal side:

First—Constables shall be ministerial officers of the courts holden by justices of the peace, in criminal cases, within their respective counties :

Second—It shall be their duty to apprehend and bring to justice, felons and disturbers of the peace, and to suppress riots, and keep and preserve the peace, within their respective counties :

Third—They shall have power, and they are hereby authorized, to execute all writs and process in criminal cases, throughout the county in which they may reside, and where they were elected or appointed :

Fourth—And if any person, charged with the commission of any crime or offence, shall flee from justice, it shall be lawful for any constable of the county, wherein such crime or offence was commit ted, and he is hereby authorized and required, to pursue after and ar rest such fugitive from justice, in any other county of this State, and such fugitive to convey before any justice of the peace of the cotmty where such crime or offence was committed.5

That’s a pretty broad set of powers. And if you go on and read the statutes, well, the list of things the constables were to do just gets longer and longer:

• summon jurors to sit on a dispute between master and servant.6

• serve writs of attachment, taking goods and money to satisfy debts and court orders.7

• serve a warrant of arrest for the alleged father of an illegitimate child.8

• summon special jurors in election contest cases.9

• levy on the goods and property of a judgment debtor.10

• return the venire (jury list) for civil trials.11

• serve an order to a poor person to leave town to prevent the person from becoming a public charge.12

• serve warrants to take charge of stray animals.13

And that’s just a sampling of the tasks given over to the constables!

Each township decided for itself how many constables it needed, and then chose the constables by election each year on the first Monday in April. Each person elected then had to take an oath or affirmation to administer the laws and faithfully and impartially discharge the duties of the office. And he had to post a bond — a written promise to do the job right — under penalty of paying a substantial amount of money, ranging from $500-$2,000 with at least one surety (co-signer) who was also a resident of the township.14

So when you find your ancestor serving as a constable — or being served with papers by a constable — you now know a little more about that position.

SOURCES

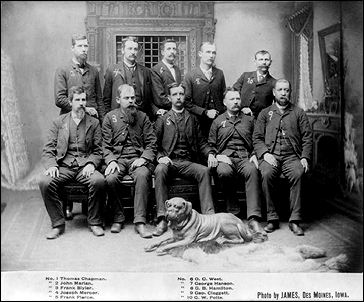

Image: “Constables the Des Moines Searchers and Advance Guard of the Fighting Prohibition Army,” c1889, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

- Humphrey H. Leavitt, The Ohio Officer and Justices’ Guide (Steubenville, Ohio: James Turnbull, 1843); digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 3 April 2017). ↩

- “Leavitt, Humphrey Howe,” History of the Federal Judiciary : Judges, Federal Judicial Center (https://www.fjc.gov : accessed 3 Apr 2017). ↩

- See e.g. 13 P.S. §40 in Pennsylvania or Ariz. Rev. Stat. §22-131. ↩

- Leavitt, The Ohio Officer and Justices’ Guide, 263. ↩

- Ibid., at 281-282. ↩

- §9, “Apprentices,” in J.R. Swan, coll., Statutes of the State of Ohio (Columbus, Ohio: State Printer, 1841), 65; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 5 April 2017). ↩

- Ibid., §§1-2, “Attachment,” at 80-81. ↩

- Ibid., §1, “Bastardy,” at 156. ↩

- Ibid., §§5-6, “Justices–Election and Resignation,” at 499. ↩

- Ibid., §66, “Justices–Civil Jurisdiction,” at 517. ↩

- Ibid., §126 at 534. ↩

- Ibid., §4, “Poor and Poor Houses,” at 635. ↩

- Ibid., §6, “Estrays,” at 872. ↩

- Leavitt, The Ohio Officer and Justices’ Guide, 262. ↩