Thou shalt not

It was a perfectly ordinary business deal, in Vermont in October of 1830. A man named Lyons bought a horse from a man named Strong.

Lyons had ridden and tried the mare out, and Strong had said the mare was perfectly sound in every way. He only wouldn’t warrant her against gravel — a type of hoof abscess. Just about evening, the two finished up the bargain, with Lyons paying an ox and a cow and three dollars in money for the mare.

Lyons had ridden and tried the mare out, and Strong had said the mare was perfectly sound in every way. He only wouldn’t warrant her against gravel — a type of hoof abscess. Just about evening, the two finished up the bargain, with Lyons paying an ox and a cow and three dollars in money for the mare.

But the deal went sour. It turned out the mare really did have gravel. And Lyons wanted damages for the breach of warranty.

Strong’s defense to the suit?

The deal had gone down on a Sunday… and Vermont law didn’t look kindly on business deals on Sunday.

The case of Lyons v. Strong went all the way to the Vermont Supreme Court where, in 1834, Chief Judge Charles K. Williams took the parties — and readers of his opinion even today — through a history lesson:

The constitution of this state, (and herein it is a transcript from the first constitution of government established in this state) while it carefully protects and guards religious freedom, and asserts that the conscience of no one can be controlled, declares, “that every sect or denomination of christians ought to observe the Sabbath or Lord’s day, and keep up some sort of religious worship, which to them shall seem most agreeable to the revealed will of God.” To carry into effect the spirit of this constitution, to enable each religious sect to keep up religious worship on the Sabbath, and to enable all to enjoy the benefits to be derived from a day of religious retirement and rest, the legislature, among their first laws, made provision for the prohibition of secular labor on that day; and in the statute which they passed in 1779, and which has in substance been continued to this time, embraced all the provisions which are contained in the English statutes of the first and second Charles. Aware of the benefits to be derived from stated periods of rest from manual labor, of the importance of having the same day observed by all, and recognizing that every denomination of christians among them regarded the Sabbath as a day set apart for moral and religious duties, they determined that every one should be protected in the enjoyment of his religious privileges and in the performance of his religious duties, and have made provision that those who are thus disposed may on that day perform those great and necessary duties which they believe are required of them, without disturbance from the secular labor of others; and further, that all, whether high or low, prisoner or free, master or servant, shall be permitted to rest, and that none shall compel them to labor on that day; and lest through avarice or cupidity, any one should be disposed so to do, they have enacted that the day shall be observed as a day of rest from secular labor and employment, except such as necessity and acts of charity shall require.1

The language Williams quoted from the Vermont Constitution — that “every sect or denomination of christians ought to observe the sabbath or Lord’s day, and keep up some sort of religious worship, which to them shall seem most agreeable to the revealed will of God” — was actually language from a 1786 amendment to Vermont’s constitution.2

The very first Constitution of Vermont, adopted 8 July 1777, had been slightly more ecumenical, providing that “every sect or denomination of people ought to observe the Sabbath, or the Lord’s day, and keep up, and support, some sort of religious worship, which to them shall seem most agreeable to the revealed will of GOD.”3

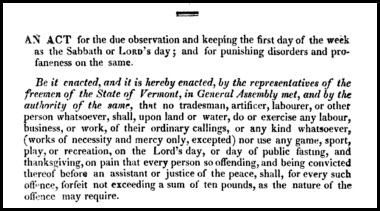

Now the statute of 1779, still in effect in 1830 when the horse trade was bargained for, didn’t expressly say you couldn’t barter for a horse on Sunday. What it did say, though, left pretty much no room for argument:

no tradesman, artificer, labourer, or other person whatsoever, shall, upon land or water, do or exercise any labour, business, or work, of their ordinary callings, or any kind whatsoever, (works of necessity and mercy only, excepted) nor use any game, sport, play, or recreation, on the Lord’s day, or day of public fasting, and thanksgiving, …

That no person shall drive a team, or droves of any kind, or travel on said day, (except it be on business that concerns the present war, or by some adversity they are belated, and forced to lodge in the woods, wilderness or highways the night before ; and in such case, to travel no farther than the next inn, or place of shelter, on that day) …4

There were other provisions imposing penalties, and particularly penalties for disturbing a worship service by things like “shouting, hollooing, screaming, running, riding, dancing, jumping, blowing of horns, or any such”,5 but the bottom line of the whole act was to keep the Sabbath day. It even went so far as to require that:

all and every assistant, justice of the peace, constable, grand-juryman, and tything man, are hereby required to take effectual care, and endeavour that this act, in all the particulars thereof, be duly observed ; as also to restrain all persons from unnecessary walking in the streets, or fields, swimming in the water, keeping open their shops, or following their secular occasions or recreations, in the evening preceding the Lord’s day, or on said day, or evening following.6

When the Court had to apply the law to the Lyons-Strong horse trade, the Chief Judge noted that “the subject under consideration is one which is liable to be viewed too much on either side through the medium of feeling; and any judicial investigation of it may be regarded as treading upon forbidden ground. A decision one way may be regarded as promoting irreligion, licentiousness and immorality; and a decision the other way be considered as encroaching upon religious freedom.”7

But, even with that concern, Williams didn’t hesitate. He held, first, that there wasn’t any doubt that a horse trade was a secular labor of employment covered by the statute. Then, he held, “a court will not lend its aid to carry into effect a contract made in contravention of a positive statute, particularly if the statute was made for the purpose of protecting the public, for promoting peace, good order, or good morals.”8

In other words, he ruled, “when there is a sale or exchange of horses made on Sunday, and a contract of warranty thereon, no action can be maintained on such warranty, it being a violation of the statute of this state.”9

Now one Supreme Court Judge, John Mattocks, disagreed, and wouldn’t have held the contract was illegal:

I believe to adjudge contracts void made on that day will not tend to the better observance of the day; that neither the common nor statute law, nor any former decisions in this state authorize, nor does sound policy require, the decision which my learned brethren have made in this cause, from the best of motives most certainly. But for myself I am not able to view the subject as they do; and I hope it is not for lack of respect for religion, or its institutions; for I believe with the Scotch covenanters, in my own neighborhood, that the law as well as a man “may like the kirk well enough without riding in the rigging.”10

But because the law was what it was, and the Court ruled what it ruled, we all know more about what our ancestors might have done — or not done — and why, at least in Vermont (and anywhere else there was a similar statute, which, by the way, was just about everywhere for a very long time in America11).

Why didn’t our Vermont ancestors do business on Sundays?

Because the law said “thou shalt not… Or else.”

SOURCES

- Lyons v. Strong, 6 Vt. 219, 221-222 (1834). ↩

- Chapter I, §III, Vermont Constitution of 1786, in Francis Newton Thorpe, The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of the States, Territories, and Colonies Now or Heretofore Forming the United States of America (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 6: 3749, 6:3752; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 27 May 2015). ↩

- Ibid., Chapter I, §III, Vermont Constitution of 1777, 6: 3737, 6: 3740. ↩

- “AN ACT for the due observation and keeping the first day of the week as the Sabbath or Lord’s day ; and for punishing disorders and profaneness on the same,” February 1779, in William Slade, ed., Vermont State Papers… (Middlebury, Vt. : J. W. Copeland, printer, 1823), 313; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 27 May 2015). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., at 315. ↩

- Lyons v. Strong, 6 Vt. at 221. ↩

- Ibid., 6 Vt. at 222. ↩

- Ibid., 6 Vt. at 229. ↩

- Ibid., 6 Vt. at 237, (Mattocks, J., dissenting). ↩

- See generally Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “lue laws in the United States,” rev. 25 May 2015. ↩

Even in my memory, Pennsylvania did not allow an inning to begin after 7 PM on Sundays.

The games would be completed at another date.

I remember voting on New Jersey’s blue law repeal, Israel — not just my lifetime, but my adult voting lifetime!

Even if the trade had taken place, say, on a Monday, I don’t see where Lyons would have had a case, if the sale was “as-is” regarding abscesses. Does the Vermont Supreme Court decision address whether the contract would have been valid if not for the Sunday issue?

Nope, it sent the case back for Lyons to try to argue that the statute ought not to apply for other reasons. It didn’t reach any issue except the legality of a contract made on Sunday.

My 5th GGF Cephas Kent ran the Kent Tavern [Inn] in Dorset, VT before the Revolutionary War. He insisted that travelers remain on Sunday and join the family’s religious observance in a room at the Inn. He would not accept arrivals on Sunday either! But he and his family prepared meals for the travelers, so I guess that fit under “great and necessary duties.”

Feeding them would certainly have been necessary!!

I live in VT, and there are times I wholeheartedly wish that there were still one day a week (I don’t care which one) in which I weren’t exposed to the noise of lawn machines, secular or otherwise, etc. I also remember the days of laws and regulations restricting commerce and other disrupting activity on Sunday (that was in Oregon), and the fuss over repeal. Some communities repealed the commerce portion, but retained some limits on disrupting activity, for the very reason that is hidden in the legal decision above: to ensure a quiet day free from the intrusions of everyday activity. Sunday admittedly is a conundrum, as not all people are christians, but I think the principle is sound, especially in this era of ubiquitous noise. By the way, it might be noted that that first Vermont Constitution was not for the state of Vermont, but for the Republic of Vermont. Vermont became the 14th state in 1791. And there is still a certain sense of independence at work here. The text of the 1777 Constitution can be seen here: https://www.sec.state.vt.us/archives-records/state-archives/government-history/vermont-constitutions/1777-constitution.aspx

Yes, Republic of, not State of, initially!

When I was growing up in Washington State in the 1950s and early 1960s, stores, including grocery stores, couldn’t be open on Sundays. I remember that law being repealed, though not the year. But state liquor stores were still closed on Sundays for years after that. I don’t know when those “Blue Laws,” as they were called here, were repealed, as I moved away in 1969. When I came back in 1997, of course everything was wide open. Only within the last few years did liquor begin to be sold in other kinds of stores, as the state liquor stores were shut down. This irks me no end, as it has some unintended negative consequence besides the obvious ones that liquor is sold where young people have easier access to it. Because liquor makes more profit for, say, a drug store, than inexpensive watches or watch and hearing aid batteries, they’re no longer available there. One argument the state made in its desire to privatize the sale of liquor was that it would make more on the tax, but in fact they’ve made less. So the state budget now has less to spend on schools. Something is wrong here, besides noisier Sundays and fewer people in church!

I feel like I’m missing something. I understand that the warranty was unenforceable because the contract was made on a Sunday, but why wasn’t the underlying agreement of purchase and sale also not found to be unenforceable? I would expect that the contract would be void ab initio, such that the parties would have been put back into the position they were in prior to entering into an illegal contract. Lyons would get his ox, cow, and $3 back and Strong would take the horse back.

The court didn’t reach the other issues, Sean: it limited its decision to the one issue brought by the appellant — whether the contract was enforceable because it had been entered into on Sunday.

Compare the following cases:

I. Matter of Samuell Allys (27 April 1674) (“Samuel Allys fed 5s. Samuel Allys of Hatfeild being presented and Complained off for Throwing a Stone at James Browne at Hatfeild on the 12th of this Instant Aprill on the Sabbath Evening alitle after evening shut in Whereby James Brown was pretty much wounded on the eyebrows. … [T]he said Samuell Allys also owning it only saying he did not intend to hurt him but only tossed it in waggery But hurt being done and it being on the Sabbath Night … I order the said Samuell Allys to pay five shillings as a fine to the County and to defray the charge of John Colemans Coming downe with him to discharge all charges …”).

Colonial Justice in Western Massachusetts (1639 – 1702): The Pynchon Court Record (Joseph H. Smith, ed., Wm. Nelson Cromwell Foundation, Harvard, Univ. Press, 1961) at 279 – 280.

II. Commonwealth v. Wolf, 3 Serg. & Rawle 48, 1817 Pa. LEXIS 10 (Upholding conviction of defendant for violating prohibition against doing business on Sunday, and finding no exception where defendant is of Jewish faith and observes Sabbath on Saturday.).

III. Matter of Congregation Darchei Noam, N.Y.L.J., 12/31/1991, p. 32 (Sup. Ct., Nassau Co. 1991) (Zoning Board’s unconditional refusal to grant parking waivers for synagogue vacated as an arbitrary and capricious failure to accommodate religious observance. “Consideration of the relief here requested, where congregants cannot drive on the Sabbath, requires special sensitivity to the First Amendment. Otherwise, they are confronted with either abandoning a practice of their religion or their homes.”).

Oooof. Sounds like a law school class final exam to me!