Recording families at birth

Two years ago, The Legal Genealogist wrote about a New Jersey court case in which the question of the hour was, who were the legal parents of a child born in what most would regard as an unconventional way?

Here were the facts:

Husband and Wife can’t have a child naturally because Wife can’t carry a child to term. Husband and Wife secure an ovum from Donor, who is anonymous, and the ovum is fertilized by way of in vitro fertilization using Husband’s sperm. Husband and Wife contract with Gestational Carrier, who agrees to have the ovum implanted, carry the ovum to term and give birth, and to give up all rights to the child. Child is born, Gestational Carrier signs the required court papers relinquishing any parental rights she may have, and Child goes home with Husband and Wife, with a birth certificate reflecting Husband as father and Wife as mother.1

The case, In re T.J.S.,2 didn’t pit Husband and Wife against Gestational Carrier. And it didn’t pit Husband and Wife against Donor either.

The case, In re T.J.S.,2 didn’t pit Husband and Wife against Gestational Carrier. And it didn’t pit Husband and Wife against Donor either.

No, the adversary who faced off against Husband and Wife was the New Jersey State Registrar of Vital Statistics — and the State’s argument was that Wife shouldn’t be listed as the mother of Child on Child’s birth certificate without going through the formality of an adoption.

Never mind that an infertile man could and can be listed as the father on a birth certificate merely by consenting in advance to the fertilization of his wife’s egg with the sperm of an anonymous donor. The Registrar thought that the infertile woman who consented to the use of her husband’s sperm to fertilize the egg of an anonymous donor had to go through a full formal adoption.

Both the trial and the intermediate appeals courts in New Jersey ruled that the language of the state statute involved meant the Registrar was right. And the state Supreme Court — understrength due to political wrangling3 — split right down the middle. In New Jersey, that means the lower court decision stands: Mom had to adopt the child to be legally Mom.

The case got me thinking, particularly about non-traditional families and how they will be treated by the law, recorded in the records we as genealogists associate with families — and documented in our software and databases. The position I ultimately took was that:

As genealogists we don’t have the luxury of punting. It’s our job to record, accurately and completely, the facts that constitute a family. And today, a family may not have Mom and Dad at all. It could well be Mom and Mom, or Dad and Dad. All of these, traditional and otherwise, are families that we must learn to document well. Along the way, our tools, our thought processes, even our hearts may need to change. But we cannot be faithful to the task we’ve undertaken if we fail to understand — or refuse to admit — that family is so much more than just bloodlines.4

After all, the Board for Certification of Genealogists, from which I hold my certified genealogist credentials and which I serve as a trustee, defines genealogy this way:

Genealogy is the study of families in genetic and historical context. It is the study of communities, in which kinship networks weave the fabric of economic, political, and social life. It is the study of family structures and the changing roles of men, women, and children in diverse cultures. It is biography, reconstructing each human life across place and time. Genealogy is the story of who we are and how we came to be, as individuals and societies.5

So I was particularly interested when, earlier this week, from reader Sean Vanderfluit of Canada came “not so much a question, but a bit of news you might find interesting. In my province, British Columbia, the law has been updated to recognize changes in parenting and non-traditional families. You can now have more than two parents listed on a Birth Registration, and the first such registration just occurred last week.”

The child in question was born to lesbian parents with the assistance of a sperm donor, but not an anonymous donor. Instead, the mothers wanted a man who would be involved as a father in the child’s life. A male friend agreed, and when the child was born, both women and the man were listed as parents on the birth registration.6

Now I’m not going to get into any discussion of whether this is a good thing or a bad thing. That’s no longer the point. The Brave New World is here, like it or not.

The question is, what are we as genealogists going to do about it? And how will our software and databases respond to the decisions we make?

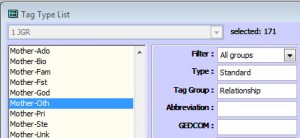

My own genealogical software, The Master Genealogist from Wholly Genes, will let me add as many people in as many relationships to the child as I wish — and I can name those relationships the way I want (not the way that, for example, the New Jersey Registrar of Vital Statistics might suggest).

Reporting can be a challenge, since there’s still an assumption that a person has two parents, and getting more than two to appear in a particular report requires some effort.

So… how are YOU dealing with this? And how does YOUR software respond to the challenge of the non-traditional in our families?

SOURCES

- Judy G. Russell, “Who’s your Mommy?,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 2 March 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 13 Feb 2014). ↩

- In re T.J.S., 212 N.J. 334 (2012), affirming by an equally divided court 419 N.J. Super. 46 (App. Div. 2010). ↩

- Do not get me started on the use of the courts as political footballs… ↩

- Judy G. Russell, 12 October 2013, address to American Society of Genealogists, Salt Lake City. ↩

- “Genealogy,” Board for Certification of Genealogists homepage (http://www.bcgcertification.org/ : accessed 14 Feb 2013). With a tip of the hat to my mentor and colleague Elizabeth Shown Mills, who posted the graphic with this very definition on Facebook today. ↩

- Catherine Rolfson, “Della Wolf is B.C.’s 1st child with 3 parents on birth certificate,” CBCNews, posted 6 Feb 2014 (http://www.cbc.ca/ : accessed 13 Feb 2014). ↩

In my family I have a non-traditional arrangement, the folks are still very much alive, where they live does not yet have a law for more than two parents. I do not know if they went through any legal guardianship at this point. My current software wouldn’t allow for this entry, but maybe I need a change. Because they are living, I would not share their information anyway.

I currently am opting to just include the biological parents in this relationship, as they are the two legally married. I save any correspondence (holiday cards etc) in my family file. Because they are living and will probably outlive me, I figure it’s the next generation to figure out . 😉 Seriously though, since it is likely the law will evolve, I will follow the law.

In other situations such as my own step-parents, and in a case where my grandmother had a biological father as well as a step father, well I recorded both of her biological (and not very nice) father, and her step father. I think some of the folks in the family would have preferred to leave off the biological father, but I have kept him in the tree, and do share that data.

It’s not my place to pass judgement. However if a non-traditional matrimonial or parenting event can not legally create paperwork it is a bit of a tricky slope. If I don’t record it, 100 years from now will anyone know?

>> It’s not my place to pass judgement.

That’s really the bottom line, isn’t it? These are families — and their judgment about that fact is the only one that matters.

Maybe I will have to update to Master Genealogist – I tried it once and it was a bit of a bear. You are right it should be documented, though I haven’t the first idea of how to do it.

Master Genealogist definitely has a learning curve. Once mastered, however (pun intended), there’s nothing you can’t do with it.

I have always used Family Tree Maker and it offers limited options for naming relationships. I’ll see if the 2014 version which I’ll be installing today has extended those options.

So far I have put information which doesn’t “fit on the form” into the Notes so that I retain it and keep it with the family information which is on the form. I can print out the family information with or without the Notes.

Keeping the non-traditional information in the notes is sure one way to handle it, Mary Ann. But our software needs to do better in the long run, that’s for sure.

Well, so, it seems to me that there are consanguinity (biology) and affinity. There was a case, I believe in the UK, in which a couple couldn’t conceive because she was incapable of transmitting functioning mtDNA. A second woman (for the mtDNA only) and a lab resulted in a healthy baby, whose total genetic package came from three people. I think it is only a matter of time before a healthy baby can be produced by combining the DNA of as many people as desired in whatever proportions are desired. (I do not comment on the morality of this.) We are going to need software that can record such (and in fact any) biological parental combinations. And then there will be DNA built in the lab from scratch and inserted. Going a bit further, it’s certainly possible that monogamy will not long be the only possibility. We may have to record legal marital relationships amongst more than two people. As to affinity: Adoption may change, but not in substance. As to families, we need to be able to record the facts, whatever they are. This means building no assumptions into the software, but allowing the user to specify roles and relationships. Or so it appears to me. Exciting times! Regards from Stuttgart, John

We certainly need software that can handle all the options, John.

Wow, that’s fascinating. I didn’t know that. It really does throw the concept of parenthood out the window. At that point, I think that “parentage” starts to be a completely different definition than “parenthood,” at least genetically. In that sort of situation, you’d really need to just sequence your DNA and point to it if someone asked you.

We kind of already have to do that!

Thanks so much for addressing the issue, Judy.

Thanks for the kind words!

I’m still trying to figure out whether and how I account for double cousins in my Family Tree Maker software.

My great-grandmother had two sisters who married two brothers; their children (and grandchildren, etc.) are first cousins (etc.) on both Mom’s side and Dad’s side.

If our basic software can’t even deal with such a situation (which is in no way unique, even a century ago), then how can we document and analyze multiplicities of parents with our software?

I’m not all that familiar with Family Tree Maker. In Master Genealogist, I can ask for a relationship calculation and find out that, for example, my direct line Baker fourth great grandfather is also my first cousin seven times removed and husband of my second cousin five times removed!

Kenneth, I have worked with Family Tree Maker for several years. A few months ago, I “had to” have a new operating system installed. It does not support the version of FTM that I had (it was pretty old) and it has taken me a long time to decide what I should do about it. If I remember correctly, if you put something in a Family Group Sheet which FTM didn’t like (e.g., James Smith m. Ann Smith), you could override it. I’m not sure whether that pertains only to the name, or to the relationship as well. The overrides which I executed seem to have everything entered correctly.

Seems like it’s a matter of three things:

1) who is the legally defined parent;

2) whose DNA contributed

3) who bore the child.

The first two apply to men and women equally, the last applies to women. So I guess you’d have to have slots for each on the birth certificates: who raises the child, who contributed genetically, and who bore them. Two slots only for 2, one for 3, multiple possible slots for 1.

You’re absolutely right — except that I wouldn’t take bets on there being only two for slot 2 in the long run.

Too complicated for my small brain; ever grateful that, thus far, I have traditional marriages, biological or adopted children in the many branches of my family tree. And, I have a hard enough time with them.

It does complicate things, doesn’t it?

I use Reunion, which is a mac application and it allows for same-sex marriages, adoptions showing both biological and adoptive parents for one one person…but as for a biological birth with three parents, I doubt it would do it. Nor should it! In the case of the lesbian couple who both their names on the birth certificate as the mother, I would want to know were some future descendant of them which mother was the birth mother. They certainly both weren’t. But that’s just me I guess. Yes, I’d want to know all about all three of them, but I’d also like to know where the bloodline actually goes too.

But we’re not recording just a biological birth here, Craig. We’re recording a family. And both of these women will be mothers to that child.

If we thought straightening out the past was a PITA at times, imagine what the future holds. Your paperwork could say one thing and your DNA another. If this problem arises in my family, I will assign the biological parents as parents and make note of any other relationships regarding that individual. In the case of donor sperm or egg, I might have to leave the parent’s identity blank. I’ve often wondered how everyone is treating illegitimate children now. I have a few that go by the married couple’s name….assuming they were adopted. If they are using their mother’s maiden name, I assume they were not adopted when she married. Even an adoption should be in the record. It’s part of family history.

My grandmother had a son that probably didn’t belong to my grandfather and later a son who probably did. I used her maiden name for the first son and her married name for the second son who was born before they married. The first son went by her married name after she and my grandfather became a family. I don’t know if there was a legal adoption after they married in 1902. Could they just change their name to match the rest of the family? That branch has all died out and there is no one left to ask.

Yes, they could just choose any name they wanted, and it was (and is today) perfectly legal as long as there is no intent to defraud a creditor or someone else.

Wasn’t there a “guide” saying “mother and baby, father maybe”? And that is provable only if someone was at the birthing and childhood and could vouch that the person was the one actually born to that mother.

And with the new technology it sounds like even this “guide” is no longer valid (grin).

So I’m guessing that most of our proven genealogy still is based on trust.

May we live in interesting times.

Oh yeah… but remember what they say in politics: trust, but verify!