The language of the law. Part Latin, part Anglo-Saxon, all confusing.

The Legal Genealogist has a couple of mantras. Things that get repeated so often, you can almost use them as a meditation chant.

One of them is: to understand the records we use, we have to understand the law at the time and in the place where the records were created. (Sound familiar, folks from the Massachusetts Genealogical Council? Whose seminar attendees probably heard it a dozen times this past Saturday?)

And the other is: to understand the terms in those records, use a dictionary from a time as close to when the records were created as possible. (Ditto for the MGC folks.)

And the other is: to understand the terms in those records, use a dictionary from a time as close to when the records were created as possible. (Ditto for the MGC folks.)

Which is why I’m always sending people off to the very first edition of Black’s Law Dictionary,1 published in 1891 and available on CD from Archive CD Books USA.

But there’s an exception to that second rule.

And I came across it again last night when I was poking around in old records.

Ancestry.com has a set of digital images online now in a database called “Washington D.C., Habeas Corpus Case Records, 1820-1863.” It’s a really neat set of records highlighting the many uses of the storied, constitutionally-based court power to bring somebody who’s in custody into court and order him set free if the custodian (jailor or sheriff or whoever) can’t establish that the person is being properly held.2

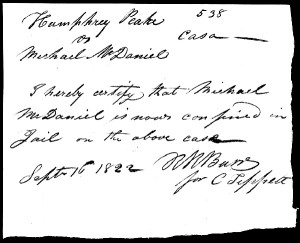

And in September 1822 one Michael McDaniel was sitting in the hoosegow in Washington County, which was what part of what was then Washington, D.C., was called.3

And, as you might imagine, he wanted out of jail.

So he petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus.4 And the court granted it.5

And one of the things that happened when a writ of habeas corpus was granted was that the U.S. Marshal for the district had to tell the court why the person was in jail. That’s the document you see above here. Michael McDaniel was in jail in a court case brought against him by Humphrey Peake. And the kind of court case: “casa.”

Casa. Casa. Hmmmmm… Somehow I suspect that this isn’t the casa of mi casa es su casa fame. As a matter of fact, I’d bet it isn’t Spanish at all.

And the real problem in trying to find a definition (because I can never remember what it means) is that it isn’t a word at all.

It’s a blankety-blank-blank abbreviation. It isn’t casa — it’s ca. sa. So you won’t find casa in the law dictionaries at all. And you won’t even find “ca. sa.” as a separate entry in Black’s earliest law dictionaries. It’s tucked away in the definition of the term for which it’s an abbreviation:

CAPIAS AD SATISFACIENDUM. A writ of execution, (usually termed, for brevity, a “ca. sa.,”) which a party may issue after having recovered judgment against another in certain actions at law.6

See, back when Black was writing his dictionary, he figured folks didn’t need separate entries for these sorts of abbreviations, because everybody knew what “casa” at the top of a legal document meant.

It’s was only in the later editions that the editors realized most folks didn’t use the legal Latin any more and certainly didn’t use the abbreviations. So you will find “ca. sa.” as a separate entry in the fourth and fifth editions of Black’s Law Dictionary. Published, respectively, in 1951 and 1979.

So if you see something like “casa” or “scifa” or some other odd-looking word in a legal document, think abbreviation. And think modern sources for a dictionary that’s most likely to explain just what the abbreviation stood for.

SOURCES

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891). ↩

- Ibid., 554, “habeas corpus.” ↩

- Judy G. Russell, “Making a county a federal case,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 22 Mar 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 21 Jul 2013). ↩

- Petition of Michael McDaniel for a writ of habeas corpus, Case No. 538, U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Sep 1822; digital images, “Habeas Corpus Case Records, 1820-1863,” Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 21 Jul 2013); citing National Archive microfilm publication M434, roll 1. ↩

- Ibid., 17 Sep 1822. ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 158, “capias ad satisfaciendum.” ↩

Cool. One of those abbreviations that “everyone should know,” except when time passes, they don’t. I’m sorry that I still don’t understand why Michael McDaniel was in jail in the first place. Someone had “recovered judgment against him”? Probably I’m easily confused. I do see that habeas corpus was granted . . . ?

Sounds like we need the rest of the story… Added to the list for the future.