It wasn’t always a holiday

In keeping with The Legal Genealogist‘s after-Christmas tradition, this post (a reprise from years past), has a question for you: Did you have a good Christmas holiday?

And, with apologies to all of our first responders and health workers and others who did have to go in over the holiday, wasn’t it terrific not having to work?

Well, all I can say is, you sure should be celebrating that day (or those days) off.

Because it certainly wasn’t always that way.

It hasn’t even been that way for very long.

First of all, forget the idea of Christmas Day as a federal holiday for most of our ancestors. The fact is, for a very long time, there weren’t any federal holidays at all. None. Nada. Zilch.1

First of all, forget the idea of Christmas Day as a federal holiday for most of our ancestors. The fact is, for a very long time, there weren’t any federal holidays at all. None. Nada. Zilch.1

It wasn’t until 1870 that a law was passed providing that New Year’s Day, Independence Day, Christmas Day, and “any day appointed or recommended by the President of the United States as a day of public fasting or thanksgiving shall be holidays within the District of Columbia.”2

And note that that law only said within the District of Columbia. It wasn’t until 1885 that federal employees outside of the federal enclave in which the capital city of Washington is located also officially got the day off.3 Oh, some departments had been closing unofficially before then4 but the law itself didn’t require it.

But, you say, surely the states recognized Christmas before then!

Well, yes, they did. But not all that much earlier. And not all of them — some didn’t come around until later.

The first law that can be identified as actually designating Christmas Day as a day off was adopted in Louisiana in 1837. It designated December 25th, among other days (including New Year’s Day, the Fourth of July and Sundays), as “day(s) of public rest and days of grace” — by which it meant a grace day for bill-paying.5

Arkansas followed in 1838, making debts otherwise payable on Sundays, Christmas Day and the Fourth of July payable one day earlier. By the Civil War, Christmas was recognized as an official holiday in most of the states.6 One of the last to name Christmas as an official holiday was Oklahoma, in 19077 — which may have been only because it wasn’t a state until then.8

Of course, this legislation was hardly the first mentioning Christmas, and some of the earlier laws even made it a day off. In Virginia, for example, in 1740, tobacco inspectors were given off on “Sundays, and the holydays observed at Christmas, Easter, and Whitsuntide.”9

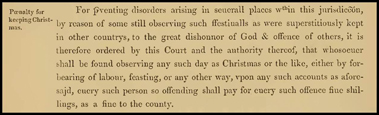

Then again some of the earlier references to Christmas were, well, shall we say, less than enthusiastic. As, for example, with the Massachusetts statute in 1659 that… well… why don’t I just let you read it for yourself:

For preventing disorders arising in several places within this jurisdiction, by reason of some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other countries, to the great dishonor of God and offence of others, it is therefore ordered by this Court and the authority thereof, that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon such accounts as aforesaid, every such person so offending shall pay for every such offence five shillings, as a fine to the country.10

For the record, Massachusetts didn’t make Christmas an official holiday until 1856.11

So don’t be surprised if you come across an official document or court record well into the 19th century featuring some action involving your ancestor on Christmas Day that has nothing to do with gifts, reindeer or figgy pudding.

SOURCES

- Stephen W. Stathis, “Federal Holidays : Evolution and Application,” Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, 8 Feb 1999; PDF version, Senate.gov (http://www.senate.gov/ : accessed 13 Dec 2016). ↩

- “An Act making the first Day of January, the twenty-fifth Day of December, the fourth Day of July, and Thanksgiving Day, Holidays within the District of Columbia,” 16 Stat. 168 (28 June 1870); digital images, “A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875,” Library of Congress, American Memory (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html : accessed 13 Dec 2016). ↩

- “Joint resolution (No. 5) providing for the payment of laborers in Government employ for certain holidays,” 23 Stat. 516 (6 Jan 1885). ↩

- Stathis, “Federal Holidays : Evolution and Application,” PDF at 2. ↩

- See Penne L. Restad, Christmas in America: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 96 and 194 n.12. The claim by James Barnett that Alabama was the first state does not appear to be accurate. See James Barnett, The American Christmas: A Study in National Culture, (New York: Arno Press, 1976), 19-20. ↩

- Ibid., 96. ↩

- §2979, “Holidays,” in Benedict Elder, ed., General Statutes of Oklahoma, 1908 (Kansas City, Mo. : Pipes-Reed Pub., 1908), 688; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 13 Dec 2016). ↩

- See Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “List of U.S. states by date of statehood,” rev. 10 Dec 2016. ↩

- “An Act, for prolonging the time for bringing Tobacco to the public Warehouses; and for the sale of Transfer Tobacco,” 1740, in William Waller Hening, The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the first session of the Legislature in the year 1619, vol. V (Richmond : 1819), 98. ↩

- Nathaniel B. Shurtleff, M.D., editor, Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England, vol. 4, part 1 (Boston: William White, public printer, 1854), 366; digital images, HathiTrust Digital Library (www.hathitrust.org : accessed 13 Dec 2016). ↩

- “An Act concerning the Observance of Certain Days,” Chapter 113, 1856, in Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Court in the Year 1856 (Boston : William White, public printer, 1856), 59; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 13 Dec 2016). ↩