Even here in the United States

It’s called, in legal parlance, a restrictive covenant.

It’s something The Legal Genealogist, and all genealogists, will encounter from time to time in the records we use to trace our family history.

The dictionary definition is pretty simple:

An agreement (covenant) in a deed to real estate that restricts future use of the property. Example: “No fence may be built on the property except of dark wood and not more six feet high, no tennis court or swimming pool may be constructed within 30 feet of the property line, and no structure can be built within 20 feet of the frontage street.” Also called “covenant running with the land” if it’s enforceable against future owners.1

A simple definition that hides what the restrictive covenant was so often used for, not so long ago, even here in the United States.

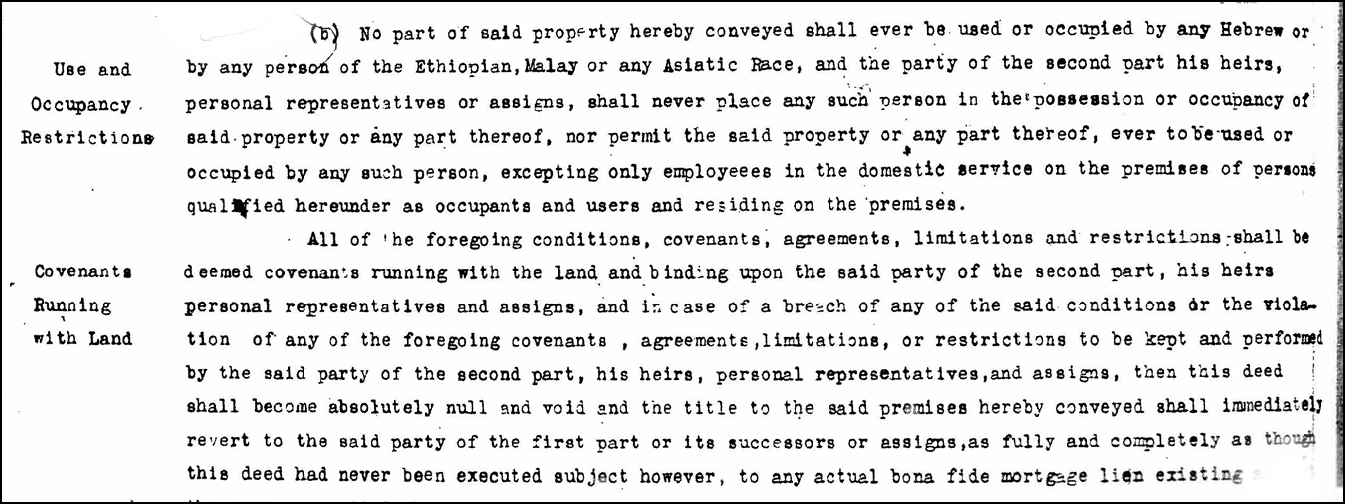

Take, for example, the restrictive covenant written into the plat map for the Jefferson Park Addition to King County, Washington, in 1927. It read:

“No person other than one of the Caucasian race shall be permitted to occupy any porttion of any lot in said plat or any building thereon except a domestic servant actually employed by a Caucasian occupant of said lot or building.”2

Or, since I’m out in Seattle today at the conference of the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies (IAJGS), how about the restrictive covenant added to the deeds for a subdivision of a five-acre tract on Clyde Hill, near Bellevue, Washington? Each deed for more than a dozen lots between 1946 and 1948 had language that said:

“This property shall not be resold, leased, rented or occupied except to or by persons of the Aryan race.”3

Or the restrictive covenant in deeds in Vermont in 1933 by a developer in the Caspian Lakes area of that state? It prohibited the sale or lease of any of the property to “members of the Hebrew race.”4

Ouch.

Not so simple any more, is it?

And, as usual, it was the law that was behind this device — both in its origins… and, in this case, in bringing its use to an end.

Before World War I, communities sought to achieve racial and religious division in housing by using zoning laws. In Louisville, Kentucky, for example, a city ordinance made it “unlawful for any colored person to move into and occupy as a residence, place of abode, or to establish and maintain as a place of public assembly, any house upon any block upon which a greater number of houses are occupied as residences, places of abode, or places of public assembly by white people than are occupied as residences, places of abode, or places of public assembly by colored people.”5

But in a 1917 decision, the United States Supreme Court struck down those laws restricting people by neighborhood based on race or, by analogy, religion. “It is the purpose of such enactments, and, it is frankly avowed, it will be their ultimate effect,” the Court said, “to require by law, at least in residential districts, the compulsory separation of the races on account of color.”6 And, it held, it was “not a legitimate exercise of the police power of the State, and is in direct violation of the fundamental law enacted in the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.”7

Those determined to draw racial and religious lines, however, seized on one line in the Court’s opinion: “That one may dispose of his property, subject only to the control of lawful enactments curtailing that right in the public interest, must be conceded.”8 And instead of public laws to restrict the sale of property to those who were in the minority by race or religion, those who wanted restrictions turned to private forms like the restrictive covenant.

Initially, the Supreme Court upheld this sort of restriction. In 1926, the Court held that the Constitution and in particular the amendments passed after the Civil War didn’t reach the actions of private individuals as to their own property: none of these amendments prohibited private individuals from entering into contracts respecting the control and disposition of their own property, it said, and it refused to consider the issue any further.9

It took more than two decades more before the Court finally held that restrictive covenants weren’t enforceable: it didn’t strike down the restrictive covenants themselves, but said that state court action to enforce a restrictive covenant violated the U.S. Constitution.10 Through that ruling, the death knell of the restrictive covenant was sounded.

Still, not so long ago, and even here in the United States, we as genealogists shouldn’t be surprised to find this kind of language in the records we research.

Not so long ago.

Even here.

SOURCES

Image: King County, Washington, Deed Book 52: 1393 (1929), Broadmoor plat map; digital image, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, University of Washington (http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/covenants.htm : accessed 10 Aug 2016).]

- Wex, Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex : accessed 10 Aug 2016), “restrictive covenant.” ↩

- King County, Washington, Deed Book 30:13 (1927), Plat map, Jefferson Park Addition; King County Archives, Seattle. ↩

- See “Aryans Only Neighborhood,” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, University of Washington (http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/covenants.htm : accessed 10 Aug 2016). ↩

- See Alan S. Oser, “Unenforceable Covenants Are In Many Deeds,” New York Times, 1 August 1986 (http://www.nytimes.com/ : accessed 10 Aug 2016). ↩

- Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60, 70-71 (1917). ↩

- Ibid., at 81. ↩

- Ibid., at 82. ↩

- Ibid., at 75. ↩

- Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U.S. 323, 330 (1926). ↩

- Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948). ↩

The post-WWII suburban development was very unusual in not having restrictive covenants written into deeds. Still, it was 15 years before African-Americans began fighting to purchase and move in.

Hard for some of us today to imagine that NOT having this kind of covenant would be the exception, rather than the norm.

Restrictive covenants may not have been legal, nor in written form, but they were maintained “informally” by real estate agents (and others) well into the 1950s and even into the 1960s. Real estate agents and/or owners could and did refuse to show/sell or rent property to a person of colour (not just African-Americans).

And redlining in the mortgage industry (not giving mortgages in “those” neighborhoods) was practiced even more recently than that. Sigh…

In the 1950s in Seattle, a friend’s family was looking for a home north of the Ship Canal. This was, and is, among the city’s prime real estate. Realtors had all kinds of excuses for not showing her parents houses there. When I asked her, she looked at me as if I was crazy not to understand. Her father was a minister at our church, which was in this area, so living there made sense. They happened to be Japanese American. A junior high student, I’d been raised to be tolerant, and I told her I thought not being able to live where you wanted wasn’t fair. She was reasonably calm about it, at least on the surface. My father explained restrictive covenants to me, which didn’t make me any happier about it. A realtor member of the church managed to find them a house and get around the restrictions somehow, because they ended up moving into a nice house north of the Ship Canal. The minister ended up on one of the local committees that worked to get restrictive covenants removed. However, Seattle remains fairly heavily residentially segregated.

Segregation is still the rule, informally, regardless of the law, and everywhere, I’m afraid.

I came across restrictive covenant language (though I didn’t know to call it that then) in a deed for property my parents bought in Ohio around 1955-56. I was appalled. And the date is almost 10 years after the Supreme Court ruled it illegal. So I am guessing that it wasn’t enforceable?

Correct: not enforceable today. But still in deeds even today.

I was shocked to find such a restriction in the deed for my parents’ small lot in post WWII Colo., on the west side of Denver. With the post-war housing shortage, their house was actually a garage. Later I discovered Dad had a mulatto ancestor 7 generations back. If only that seller had known!

You’ll see that sort of language in deeds way late, Jim — and it’s always a shock.

I don’t know anything about Kansas laws but when my family moved from our Colorado farm to the small town of Ottawa, in northeastern Kansas, (where my dad would earn his college degree in 3 1/2 years) in January/very early February of 1953 there was no student housing available so we rented a small house in a neighborhood. An African-American woman lived on one side of us and she and my mother became fast friends while chatting over the clothes lines. Next door to her was a CME church which was very small but had a very wonderful choir. I was not feeling very well one Sunday morning and my mother let me stay home. There was no air conditioning then so everybody’s windows were open and when that choir sang I fell in love with the sound! After that I would plead an upset stomach as an excuse to stay home and listen to the choir. I was only able to pull it off a couple of times, but it’s a wonderful memory that I always carry with me.

Wonderful memory, Mary Ann!

Thank you for covering this topic. You might like the work being done in DC to uncover and map all the restrictive covenants and deeds. This is an excellent web site to see the work to date: http://jmt.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=061d0da22587475fb969483653179091

Good resource, thanks.