More New Deal era records for us to use

Yesterday’s post on the New Deal had reader G R Berry thinking about other records from that time period that are useful for genealogy.

“The New Deal also produced records we can use,” the reader pointed out. “For example, the Work Projects Administration, Division of Community Projects, National Archives Project compiled all the data from ship registrations and enrollments in the customs district of Machias Maine and published them as a book. These records include ownership data. Looking at Hathi Trust’s catalog for that author, they also did similar books for a bunch of other customs districts. Hathi Trust has 978 full view items for a search on Works Project Administration, including titles like ‘The skill of brick and stone masons, carpenters, and painters employed on Works Progress Administration projects in seven cities in January, 1937’, ‘Landplatting in Duluth, Minnesota, 1856-1939,’ ‘Guide to ten major depositories of manuscript collections in New York State (exclusive of New York City)’, ‘Guide to vital statistic records in Arkansas’, ‘Jackson County, Indiana index of names of persons and of firms’, or ‘Annals of Cleveland, 1818-1935; a digest and index of the newspaper record of events and opinions’…”1

Oh, yeah. And those off-the-beaten-track bits and pieces pointed out by this reader don’t even begin to describe the goodies we as genealogists have because of the Works Progress Administration.

Oh, yeah. And those off-the-beaten-track bits and pieces pointed out by this reader don’t even begin to describe the goodies we as genealogists have because of the Works Progress Administration.

The Legal Genealogist has noted the WPA as a genealogical resource before,2 but it’s clearly time to review this topic again.

First established under and funded by the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935,3 its work wasn’t nearly done when, on 21 June 1938, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed into law the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 19384 that allowed the WPA to continue — and to create some of the most amazing genealogical resources that will ever exist.

Most of us probably know that the Works Progress Administration (“WPA”) was a massive federal project to put people to work in the depths of the Great Depression. It employed millions of Americans on public projects sponsored by federal, state, or local agencies, and as World War II loomed and then began, on defense and even war-related projects.5

And in the course of that effort to put people to work, the WPA hired teachers, historians, clerical workers, writers and photographers to document America as it was and to survey what it had been.

There are three major results of the WPA’s works for which today’s genealogists can be forever grateful.

First, the Historical Records Survey produced a wide variety of inventories of available vital records, plus bibliographies, cemetery and newspaper indexes. It produced inventories of manuscript collections in archives, historical societies and libraries, public and private. It inventoried church records. It produced indexes to censuses and naturalization records. It produced place-name guides. And these records are widely available around the country and on microfilm through the Family History Library.

You want to know about changes in street names in New Orleans between 1852 and 1938? There’s a typewritten volume, Alphabetical Index of Changes in Street Names, Old and New Period 1852 to Current Date, Dec. 1st 1938, prepared by the WPA that’s now online at the Louisiana Division of the New Orleans Public Library.

Want an index to the Blount County, Tennessee, Burial Records? One was prepared by the WPA — it’s in the Tennessee State Library & Archives.

How about an index to birth records from Starke County, Indiana, from 1894-1938? It’s there in the Indiana State Library. Along with the WPA-prepared index to marriage records, 1896-1938, and index to marriage transcripts, 1899-1938.

Want to know what records existed — and exist — in Oklahoma? There’s a catalog of American Indian records found at the Oklahoma Historical Society, inventories of federal documents in the Veterans Administration, post offices, relief agencies, and federal courts, inventories of records in all seventy-seven counties and of municipal records, church archives and private collections within the state — and most of the records of what was done are located in the Research Division of the Oklahoma Historical Society.6

In Missouri, there are now 302 linear feet of records, or 817 rolls of microfilm of the Historic Records Survey — correspondence, essays, forms, instructions, lists, publications, reports, research material, and notes — at the State Historical Society.7

In Texas, the Historical Records Survey handled “the renovation and rearrangement of more than ten million documents and 362,452 volumes; the transcription of 217,323 pages of records dating from 1731; the preparation of new name or subject indices to 1,169,762 property records and name indices to over four million birth, death, and marriage records; the preparation of new name indices to supplement the original recordings of 928,900 district and county court records; and the inventory of probate case papers for 392,450 estates as a means of assisting interested persons in finding these valuable documents.”8

There are the folks who did the soundex indexing of the 1920 census, undertaken as a Historical Records Survey project of the WPA in New York City. Literally thousands of WPA workers were assigned to that project starting in 1938; it wasn’t finished until 1940.9

But that’s not all genealogists can thank the WPA for. There’s also the Federal Writers’ Project. It may be best known for having produced a series of guide books of the states now known as the American Guide Series. The U.S. Senate has a description of the series online, but focusing on the guides barely begins to do the work of the Federal Writers’ Project justice. In addition to the guide books, there were local histories produced, compilations of folklore, books and pamphlets for children and adults and — best of all — all kinds of interview reports.

Want to know where James H. Armstrong of Ogalalla, Nebraska, was born in 1828? Or what happened to the crops there before they could be harvested in 1887? Check out the interview with his daughter, Ada Case, who was interviewed 14 November 1938.10

How about Mr. and Mrs. Charles Gaston of Ogalalla? Check out the 1938 interview with Mrs. Gaston. You’ll discover that he was born 2 May 1859, at Saskatchawan, Canada, and came to Keith County in 1884. She was born 15 November 1869 at La Port Indiana. They were married at Grant Nebraska, 1888, moved to Happy Hollow and had six children: John Franklin in 1892; Isac Iver, 1894; Katherine Marjria, 1896; Charles Adam, 1890; Kenneth Lloyd, 1902; and Dicy Dorritt, 1906. Most of their life story is there.11

The Slave Narratives may be the most compelling of the oral histories. There are 17 volumes in the series compiled by the WPA entitled Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. And they’re online at the Library of Congress’ American Memory Project in a collection called Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938.

Mrs. John High of Arkansas was interviewed in 1938 and told of Emiline Waddell, former slave of the L.W. Waddell family, born in 1826 in Rabun County, Georgia, a slave of Claybourne Waddell. She was reportedly born a deaf mute but had hearing and speech restored when lightning struck a tree under which she was standing.12

Addie Vinson of Athens, Georgia, told of her father Peter being bought from Sam Brightwell by Ike Vinson. Her father’s parents were Grandma Nancy and Grandpa Jacob, slaves of Obe Jackson. And she spoke of her life and the life of other slaves, such as the way the overseer beat the slaves; once her uncle was beaten so badly he couldn’t work for a week.13

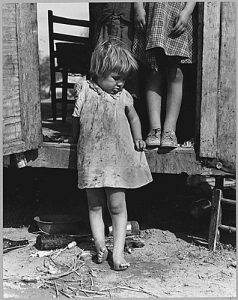

And even that’s not all to thank the WPA for. There are also the photographs. Hundreds and hundreds available through the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog. Thousands more available at the National Archives. Thousands more than that available through online sources such as the New Deal Photo Gallery at the New Deal Network as featured yesterday.

And then there are all those off-the-beaten-track bits and pieces pointed out by reader G R Berry.

All of these wondrous bits and pieces and resources of the WPA.

Where would we be without them?

SOURCES

Image: Arizona child, photographed by WPA, 1930s.

- GR Berry, Comment to Judy G. Russell, “Such a deal!,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 22 June 2016 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 23 June 2016). ↩

- ibid., “Thanks for one government ‘boondoggle’,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 21 June 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 23 June 2016). ↩

- 49 Stat. 115. ↩

- 52 Stat. 809. ↩

- See generally Final Report on the WPA Program 1935-1943 (Washington, D.C. : Government Printing Office, 1947); digital images, Library of Congress Digital Collections (http://www.loc.gov/library/libarch-digital.html : accessed 22 Jun 2016). See also Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Works Progress Administration,” rev. 16 Jun 2016. ↩

- “Historical Records Survey,” Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture, Oklahoma Historical Society http://www.okhistory.org/publications/encyclopediaonline.php : accessed 22 Jun 2016). ↩

- U.S. Work Projects Administration, Historical Records Survey, Missouri, 1935-1942 (C3551), State Historical Society of Missouri (http://shsmo.org/ : accessed 22 Jun 2016). ↩

- Texas State Historical Association, Handbook of Texas Online, “Texas Historical Records Survey,” (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online : accessed 22 Jun 2016). ↩

- Claire Prechtel-Kluskens, “The WPA Census Soundexing Projects,” Prologue Magazine, Spring 2002, Vol. 34, No. 1; online, Archives.gov (http://www.archives.gov : accessed 22 Jun 2016). ↩

- Ada Case, interview, 14 Nov 1938; transcript and digital images, “American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940,” Library of Congress, American Memory (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html : accessed 22 Jun 2016). ↩

- Ibid., Mrs. Charles Gaston, interview 5 Sep 1938. ↩

- Mrs. John G. High, interview, 20 Oct 1938; transcript and digital images, “Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938,” Library of Congress, American Memory (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html : accessed 22 Jun 2016). ↩

- Ibid., Addie Vinson, interview, 23 Aug 1938. ↩

Hi Ms. Russell,

I haven’t taken a DNA test but I really want to. But, my paternal great uncle did. This paternal great-uncle is my father’s father’s brother. He was told he was Y haplogroup C3 (now C2, I think because someone said they changed the name in 2016). I was wondering if I would have this paternal Haplogroup too. Thank you so much!

Each man should have the same YDNA haplogroup as his father. So all of you who descend from the same man (in this case all men who descend from your father’s father’s father — including your grandfather, your grandfather’s brother, your father and you) should all share the same haplogroup.

Thank you so much! Is this Haplogroup common in Southern Germany? My paternal line originates in Bavaria.

Thank you for this piece. I have benefited greatly from the work of the WPA on the cemeteries in Savannah. Sounds like I better start checking out more WPA records. I think much of this is now available online but I used it 15 years ago. The librarians in Savannah would send me all the pages I wanted if I provided a surname. Librarians are another much overlooked and un-thanked resource

Another great resource created by the WPA is the Texas county scrapbooks, available at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. Here is a link: http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utcah/00557/cah-00557.html

These scrapbooks are full of newspaper clippings, including obituaries, “old settlers’ reunions, Civil War veterans reunions, etc. They are wonderful! Important note: the Briscoe Center is undergoing renovations. They are still open in another facility on campus. If you plan to go, be sure to call first, as you must make an appointment and request materials in advance. Here is a link to their site: https://www.cah.utexas.edu/index.php

Does anyone know the copyright status of the material from the various WPA projects? I read that some of the writers retained their copyright even though employed by the federal government.

The WPA county histories are transcribed on a number of sites. We have a lady in Mississippi who posts them and claims a copyright on the transcription of the WPA materials.

One of the rural churches in Alabama is painted with wonderful Bible murals done by a WPA artist. He got stranded in rural Alabama on his way to a federal job and did the work for travel money. It is now an historical site.

Federal law expressly provides that there is no copyright in materials created by federal government employees for the federal government.

The American Guide Series brought up this question.

New Orleans City Guide written and compiled by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration.

Copyright 1938 by the Mayor of New Orleans All Rights Reserved including the right to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form.

It appears some of the WPA items were joint ventures and non-federal organizations claimed copyrights over the WPA federally funded work by federal employees.

I will look at other guides in that WPA series to see what the pattern is. This may be a moot point since most of these 1930s copyrights have expired.

I repeat: nothing done by federal government employees for the federal government can be copyrighted. Period. Anybody can CLAIM copyright. But if it was in fact “federally funded work by federal employees” then it never was copyrighted.