A rare turn of phrase

The Legal Genealogist often joins the rest of the genealogical community in whining about legal Latin.

But the Romans are not the only ones we have to blame for obscure language in legal documents we come across.

But the Romans are not the only ones we have to blame for obscure language in legal documents we come across.

And sometimes what we come across just leaves us shaking our heads.

A case in point comes from an opinion of the United States Supreme Court.

The case — Kungys v. United States1 — is an interesting case, all by itself. It involved an attempt by the government to denaturalize — take away the naturalized citizenship — of a man accused of participating in World War II atrocities and of lying in his initial papers seeking to come to the United States from Europe after the war.

The government advanced three reasons at the trial court level why this naturalized citizen, Juozas Kungys, should be stripped of his citizenship: first, his participation in the atrocities; second, that he had made false statements about when and where he was born, his wartime occupations, and wartime residence; and third, that he lack good moral character because of the lies.

There were all kinds of twists and turns in the case: the government failed to produce the kind of evidence the trial court could consider about the atrocity allegations; the trial court rejected the false statements claim because, it said, the kinds of false statements weren’t material, and since they weren’t material, they didn’t show bad moral character.

The Third Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the trial court about the atrocity allegations, but disagreed on the question of whether the false statements were material.

So when the case got to the Supreme Court, the whole thing came down to one real point: what did the term “material” mean in this context?

And that’s where the oddball case in point came in.

The opinion in Kungys v. United States, authored for the majority by Justice Antonin Scalia, solemnly concluded that: “The term ‘material’ in (the immigration statute) is not a hapax legomenon.”

R-i-i-i-i-i-g-h-t.

What the heck is a “hapax legomenon”?2

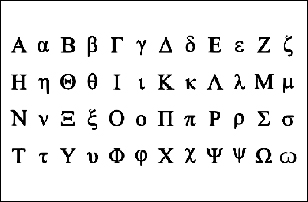

I’ll tell you right now, don’t bother looking in the Latin-to-English dictionaries, because it isn’t a Latin-derived term. It’s Greek.

And don’t bother looking in the law dictionaries, either: the term isn’t there.

Np, you’re going to have to go to the regular dictionaries for this one, and there you’ll find that it’s a “word or form occurring only once in a document or corpus,”3 or a “term of which only one instance of use is recorded.”4

So what Justice Scalia was saying was that the word was used in many parts of the law, and had a generally known meaning that shouldn’t be monkeyed with in the context of the immigration laws.

He chose to do it with a term that nobody else was likely to understand without looking it up.

Because, you see, the term “hapax legomenon” is a hapax legomenon.

Sigh…

Even to this genealogist with a law degree, the language of the law is occasionally a mystery…

Oh, and by the way… Kungys voluntarily surrendered his citizenship to avoid deportation and died in the United States in 2009.5

SOURCES

- Kungys v. United States, 485 U.S. 759 (1988). ↩

- Friend and fellow genealogist Vicki Wright suggested on Facebook that it sounded like a Harry Potter curse. Facebook, comment on J. Russell status by Vicki Wright, posted 31 Mar 2015. ↩

- Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (http://www.m-w.com : accessed 1 Apr 2015), “hapax legomenon.” ↩

- Oxford Dictionaries Online (http://oxforddictionaries.com/ : accessed 1 Apr 2015), “hapax legomenon.” ↩

- See Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “List of denaturalized former citizens of the United States,” rev. 29 Mar 2015. See also Social Security Death Index, entry for Juozas Kungys (1913-2009), Mocavo.com (https://www.mocavo.com/ : accessed 1 Apr 2015). ↩